Hours after the Canadian men’s soccer team officially qualified for the World Cup last month, Canadian Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez took to Facebook to celebrate the win. The Rodriguez post included a link to a La Presse article on the game (the same link I’ve just posted). Visitors that click on the link are taken to the newspaper’s website, shown a series of ads, offered some encouragement to subscribe, and presented with a series of widgets they can use to also post the link to Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn. While there is nothing unusual about that in today’s media economy, yesterday Rodriguez introduced a bill that would fundamentally alter the activity. According to Rodriguez, Facebook should pay La Presse for the link that he posted and his Bill C-18, the Online News Act, would create a mandatory arbitration system overseen by the CRTC to ensure that they do.

Pablo Rodriguez Facebook post, https://www.facebook.com/HonPabloRodriguez/posts/389066676372209

There is much to unpack about the provisions in Bill C-18 – the enormous power granted to the CRTC, the extensive scope of the bill that could see services such as Twitter, LinkedIn, Bing forced to pay for links posted by their users, and the provision that encourages the Internet platforms to dictate how Canadian media organizations spend the money among them – but at the heart of the bill is the principle that news organizations should be compensated by some entities for links that refer traffic back to them. Indeed, Rodriguez had the following exchange with Evan Solomon yesterday:

Solomon: Can you justify why links are compensatory?

Rodriguez: Because there’s a value to that. If you click on the link and go to the news, there’s a value to that.

Of course, not all links have that value. If the principle was that links have value requiring compensation, then why shouldn’t I be required to pay for linking to the same article? Why should the platform be required to pay and not the person that posted the link? The government isn’t interested in requiring me to pay for a link, however, only large Internet companies who refer millions of users back to the media sites. In other e-commerce sectors, recipients of the in-bound traffic often pay for the referrals, since they can generate revenue from the visits. In Bill C-18, the government flips that on its head by holding that the party enabling the referral must pay for the privilege of doing so.

The fact that the media sector already receives value from the referral link is evident by its actions. Late last year, News Media Canada ran a webinar on reviving newspapers in digital news deserts. The key recommendations:

- Help Google index your site

- Get headlines to appear in Google News

- Direct traffic from Facebook to your website

- Keep readers engaged on the website longer

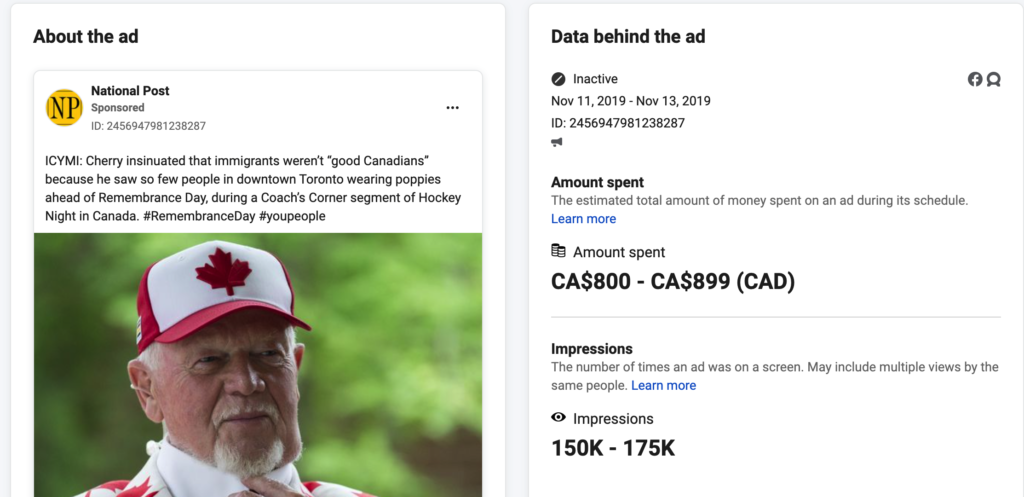

The lead lobbyist for Bill C-18 is telling its members to prioritize Google News and Facebook, yet somehow arguing that those free services are unfairly benefiting from the very links they post and encourage. In fact, the news sector values those referral links so much that they are willing to pay for them. For example, here’s Postmedia spending hundreds of dollars on a Facebook ad simply to drive traffic to one of their articles.

Facebook Ad Library, https://www.facebook.com/ads/library/?active_status=all&ad_type=all&country=CA&q=postmedia&search_type=keyword_unordered&media_type=all

The truth is that no one should pay for the link. As the Supreme Court of Canada stated in Crookes v. Newton, a case that examined links in the context of defamation:

Hyperlinks thus share the same relationship with the content to which they refer as do references. Both communicate that something exists, but do not, by themselves, communicate its content. And they both require some act on the part of a third party before he or she gains access to the content. The fact that access to that content is far easier with hyperlinks than with footnotes does not change the reality that a hyperlink, by itself, is content-neutral – it expresses no opinion, nor does it have any control over, the content to which it refers.

The court added:

The Internet’s capacity to disseminate information has been described by this Court as “one of the great innovations of the information age” whose “use should be facilitated rather than discouraged”. Hyperlinks, in particular, are an indispensable part of its operation.

So concerned was the Supreme Court of Canada with the importance of links that in considering potential liability for defamation for a link, it warned “given the core significance of the role of hyperlinking to the Internet, we risk impairing its whole functioning.”

The Canadian government and Minister Rodriguez do not seem particularly concerned about the harm to the Internet that Bill C-18 could cause. In fact, for the purposes of the bill, there is no difference between posting an article or linking to it, since it is all “making available of news content.” That is defined as:

For the purposes of this Act, news content is made available if

(a) the news content, or any portion of it, is reproduced;

or

(b) access to the news content, or any portion of it, is facilitated by any means, including an index, aggregation or ranking of news content.

It should noted that there is no debate over reproduction. The Internet platforms already license news content where it is reproduced in full with many deals between Canadian publishers and companies such as Google and Facebook. But Bill C-18 seeks to extend the requirements to license by requiring payments for links, despite the absence of any valid legal claim for the need to do so. In fact, the government is already saying that previous agreements may need to be renegotiated in light of the bill. With these provisions, the government takes aim at the basic right to share information online – a core aspect of the Internet – by imposing a requirement on Internet platforms to obtain a licence for linking.

Further, this broad definition is not limited to linking to actual news articles. If the standard is facilitating access to news content by any means, then simply linking to a news site itself would seem to qualify. That is astonishingly overbroad and damaging to the Internet, effectively saying that a link to the homepage of a website might require compensation if the link appears on DNI’s service.

I wrote in great detail yesterday about why the bill is bad for press independence and competition. That post examined the implications of the policy for press independence, competition and innovation, compensation without value, reliance on big tech, and administrative and governance risks. Now that Bill C-18 is available, it is even worse that expected.

Rodriguez insists that the government is supporting a market-based approach, but nothing could be further from the truth. The bill identifies which “digital news intermediaries” (DNI’s) are subject to the mandated requirements for payments, referencing whether there is a “significant bargaining power imbalance” with reference to the size of the intermediary, whether the intermediary has a “strategic advantage” over news businesses, and whether the intermediary occupies a prominent market position. There isn’t much guidance on what any of this means, so there is a plausible case that it extends far beyond just Google and Facebook to include services such as Twitter, LinkedIn, Apple News, and Bing among others. Since Twitter is dominated by sharing links, Canadian news organizations could certainly pursue payments. Interestingly, it is up to the DNI’s themselves to notify the CRTC if they believe the Act applies to them.

On the other side are “eligible news businesses” or a group of eligible news businesses, since there is the power to negotiate collectively. An eligible news business is is defined as either a Qualified Canadian Journalism Organization (a definition from the Income Tax Act) or a business that meets similar requirements as the QCJO (general interest news content production, 2 or more journalists, operate in Canada, news not limited to a specific topic). This can include both public and private broadcasters and the inclusion of the definition of a QCJO without Canadian ownership requirements suggests that the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and other foreign news services may qualify. Including U.S. media giants in the bill may help with a trade challenge, but is not going to do anything to address the policy objectives of helping local news.

These businesses are given the power to start a bargaining process for payment. If unable to reach an agreement, the bill provides for a final offer arbitration process administered by the CRTC. Far from a “market based” approach, the bill even requires the arbitrators to reject offers that fail to live up to the government’s standards (for example, it doesn’t “enhance fairness in the Canadian digital news marketplace”).

The alternative to mandated arbitration is to strike a deal. But the bill requires that the CRTC approve any deal in order to avoid the legislated bargaining process and, as noted, the government already thinks that some previous deals will need to be renegotiated. The standards of approval extend far beyond “fair compensation” to also include:

(ii) they ensure that an appropriate portion of the compensation will be used by the news businesses

to support the production of local, regional and national news content,

(iii) they do not allow corporate influence to undermine the freedom of expression and journalistic independence enjoyed by news outlets,

(iv) they contribute to the sustainability of the Canadian news marketplace, and

(v) they ensure a significant portion of independent local news businesses benefit from them, they contribute to the sustainability of those businesses and they encourage innovative business models in the Canadian news marketplace,

vi) they involve a range of news outlets that reflect the diversity of the Canadian news marketplace, including diversity with respect to language, racialized groups, Indigenous communities, local news and business models; and

(b) any condition set out in regulations made by the Governor in Council.

What makes this list remarkable is not just that the government claims it provides a “market based” solution and then proceeds to have the CRTC approve all deals based on these standards. Rather, approval of any deal only comes when the DNI – the Internet platform – applies to the CRTC to request an exemption order from the bargaining process. It is the Internet companies that must prove that the deal will ensure that a significant portion of the compensation will be used to support local production of news content. In other words, the government’s solution to concerns about powerful Internet companies is to grant them even more power by requiring them to specify how Canadian news organizations spend their money.

Bill C-18 doesn’t only increase the power of the Internet companies. It also provides exceptional new powers to the CRTC. These include determining which entities qualify as DNIs, which agreements create an exemption, which Canadian news organizations qualify as eligible news businesses, and whether the arbitration decisions should be approved. On top of that, the CRTC will also create a code of conduct, implement the code, and wield penalty powers for failure to comply. Far from a hands-off approach, the CRTC will instantly become the most powerful market regulator of the news sector in Canada.

The bill also features some concerning provisions that need further explanation. For example, there is a copyright provision that appears to limit the applicability of fair dealing, providing that limitations and exceptions do not limit the scope of the bargaining process. That provision might be used to demand payments for uses that do not require compensation under the Copyright Act and could provide a dangerous model to override Supreme Court jurisprudence. The definition for eligible news businesses also requires further unpacking, including the need for confirmation that large foreign news services may qualify. And while on this issue, why is there an option for those new businesses to withdraw their consent for publicly disclosing the fact that they are on the CRTC list of eligible news businesses?

A preliminary review of the bill would not be complete without referencing one positive, namely a prohibition on discrimination, preference and disadvantage. Section 51 states:

In relation to news content that is produced primarily for the Canadian news marketplace by a news outlet operated by an eligible news business and that is made available by a digital news intermediary, the operator of the intermediary is prohibited from acting in any way that

(a) unjustly discriminates against the business;

(b) gives undue or unreasonable preference to any individual or entity, including itself; or

(c) subjects the business to an undue or unreasonable disadvantage.

That is an excellent starting point for addressing the actual concerns of the platforms and news media. Yet despite that provision, the biggest problem comes back to the fundamental premise of a bill that purports to help the Canadian news business, but ultimately takes aim at sharing information online by mandating payments for the simple yet essential step of linking to a news article.

What are they thinking at the federal cabinet table?

That’s easy. They are thinking “How can I keep the money rolling in from the lobbyists?”

What is the news? It’s an important question because much of what appears on news organizations’ websites is not news or, at best, can be described as soft news. So will compensation have to be paid for links to comic strips, editorials, letters to the editor, opinion columns, weather reports, movie reviews, recipes, sports scores, celebrity gossip, classified ads, horoscopes, etc that appear on news organizations’ websites?

Twitter gets money on ads/etc on their page in which there’s a news link. Fine.

You click on link, end up in the news site, it gets money on it’s own ads/etc. Fine.

Where’s the problem? They all get money. One of them (news site) even gets free referral/discoverability.

We end up costing money to Twitter because we put a link.

It will not have a problem or start censoring/limiting content because of this lunacy?

What happens, in the current international conflict, if there’s a link on twitter pointing to cbc.ca and cbc.ca mentions reuters who them mentions a local news agency article?

We don’t do this kind of thing irl, So why do it on internet? Because we have the technical means?

I just find this bill is startlingly problematic. If care isn’t taken, it might even stifle free speech.

Pingback: BILL C-18: Mainstream media could see colossal payday - The Counter Signal

Pingback: 917 Budget Day Speculation, C18 Censorship, Travel Restrictions and More - CanadaPoli

Pingback: Canadians could soon be restricted on Facebook because of Bill C-18 - The Counter Signal

Pingback: As más lições do projeto canadense de remuneração do jornalismo – Bruno Dalólio Advocacia