The government’s online harms bill – likely rebranded as an online safety bill – is expected to be tabled by Canadian Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez in the coming weeks. The bill, which reports suggest will even include age verification requirements that raise significant privacy and expression concerns, is expected to emerge as the most controversial of the government’s three-part Internet regulation plan that also includes Bill C-11 and Bill C-18. Given the fierce debate and opposition to those two bills, it may be hard to believe that online harms or safety will be even more contentious. Yet that is likely both because the bill will have enormous implications for freedom of expression and because Canadian Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez and his department face a significant credibility gap on the file. To be absolutely clear, there is a need for legislation that addresses online harms and ensures that Internet platforms operate in a transparent, responsible manner with the prospect of liability for failure to do so. However, Canadian Heritage has repeatedly fumbled the issue with conduct that raises serious concerns about whether it is fit to lead.

There are many concerns that I could focus on – the misleading Bill C-11 claims, the failure to account for the policy risks in Bill C-18 that could lead to blocking of news sharing in Canada on Internet platforms, Rodriguez’s inexplicable silence in the face of Canadian Heritage funding an anti-semite, the Parliamentary Secretary for Canadian Heritage’s amplification of misleading information and labelling critics as racists or seeking their investigation – among them. But this series of posts will be limited specifically to how the online harms policy has been developed within the government, most notably at Canadian Heritage. Documents released under Access to Information and a careful review of government “summaries” point to a pattern of failing to fully brief Canadians on the policies and their development.

This first post starts with the aftermath of the 2021 consultation on online harms, which was designed to provide the foundation for the bill. The consultation was launched by then-Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault in the summer, running for much of the 2021 election campaign (my submission here). The consultation attracted widespread criticism with the government surprisingly refusing to disclose the actual submissions, implausibly citing concerns about confidential business information. Instead, it posted a “What We Heard” report that omitted key criticisms and dramatically understated the public concern with the government’s proposed plans. The actual submissions were released only once the government was legally compelled to do so under the Access to Information Act. I obtained a copy of the responses under ATIP, revealing that the criticism had been far more significant than previously disclosed. Indeed, companies such as a pre-Elon Musk Twitter had likened the parts of the plan to policies found in China, Iran, and North Korea.

But beyond the hidden submissions, I have now obtained further documents under the Access to Information Act that indicate the government was telling Canadians one thing and internal department executives something else. Consider the top-line takeaway summary in the What We Heard Report:

There was support from a majority of respondents for a legislative and regulatory framework, led by the federal government, to confront harmful content online.

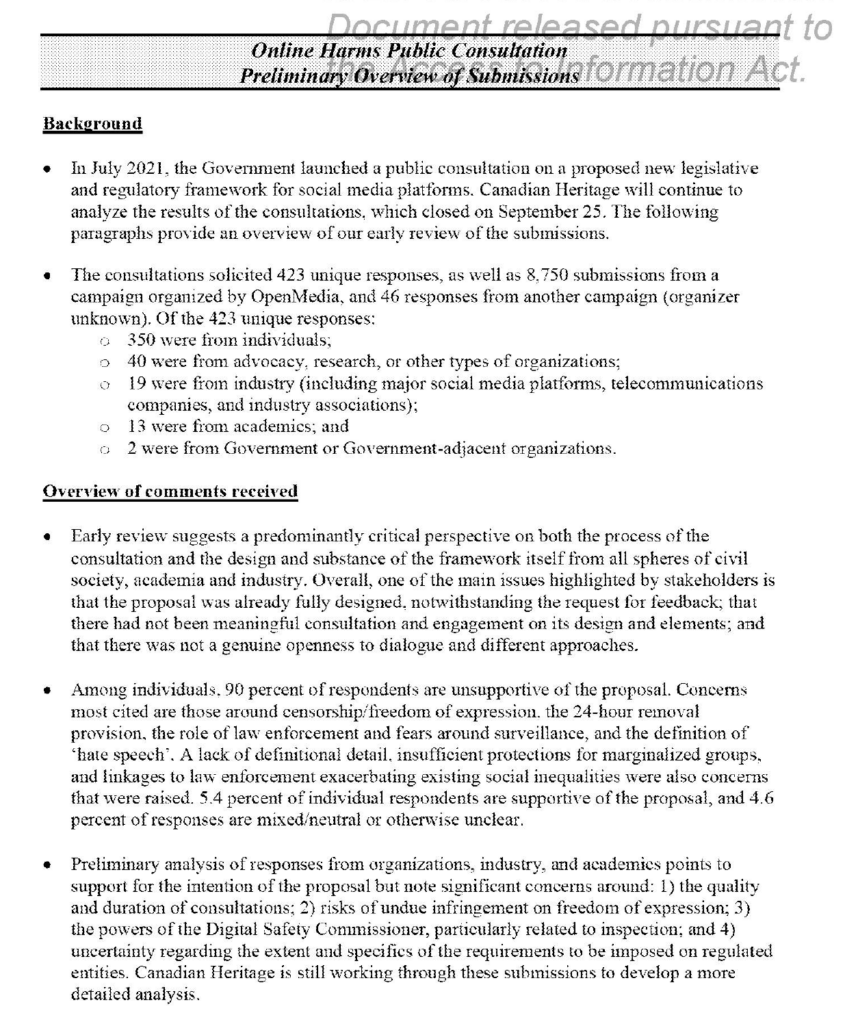

The internal summary, posted below, told a much different story:

Among individuals, 90 percent of respondents are unsupportive of the proposal…5.4 percent of individual respondents are supportive of the proposal and 4.6 percent of responses are mixed/neutral or otherwise unclear.

There is no reference to 90% opposition in the What We Heard report. In fact, the document indicates there were 350 individual responses, suggesting that only 19 Canadians provided supportive responses to a nationwide public consultation on a key government policy issue. Indeed, the internal summary overview clearly became the source for the “public consultation highlights” in the public report but at every turn, the department downplayed the public criticism. The 90% opposition is reframed as “there was a blend of positive and negative responses, though there was a predominantly critical perspective”. A reference to “there was not a genuine openness to dialogue and different approaches”in the internal document was cut from the public version. Similarly, a reference of concerns that that proposal’s “linkages to law enforcement exacerbating existing social inequities” was not included in the public version.

These differences suggest Canadian Heritage kept the public in the dark by denying release of the public submissions and then posting a summary report that omitted crucial information. Given the need for trust in developing online harms proposals, it alone could be viewed as disqualifying. Yet as this series will document, it was only the start of a deeply flawed process that has badly damaged the government’s credibility on the online harms issue.

Pingback: Links 13/04/2023: Nanonote 1.4.0 and LWN Looks at Mobian | Techrights

Pingback: Canadian Government Departments Pressure Social Media Sites to Censor News Links, Mean Tweets | Sassy Wire

Pingback: Links 13/04/2023: Stable Kernels and Alyssa Goes to Dyson | Techrights

What is the accuracy of these reports?.

Pingback: Tucker, the Left, and Poor Old Canada – PJ Media

Pingback: Tucker, the Left, and Poor Old Canada – American Patriots For Change

Pingback: Tucker, the Left, and Poor Old Canada By David Solway | RUTHFULLY YOURS

Pingback: Trust – PJ Media

Pingback: Trust – American Patriots For Change

Pingback: TRUST: BY DAVID SOLWAY | RUTHFULLY YOURS

Pingback: Trust | peckford42