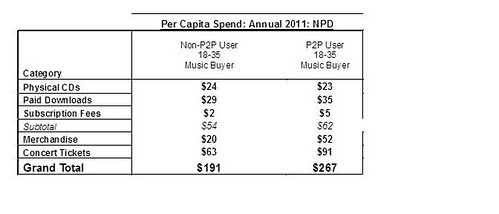

File sharing of music has been part of the Internet landscape for well over a decade, but the debate over its economic impact continues to rage. The issue has come to fore once again in recent weeks after Columbia University’s American Assembly released an excerpt of a report that found that peer-to-peer users purchase 31 percent more downloads than non-P2P users. The NPD Group, which conducts industry analysis for the Recording Industry Association of America, quickly responded with data that purports to show that among music buyers, both P2P and non-P2P users spend about the same, though P2P users spend more on merchandise and concert tickets. The NPD Group dismisses the additional spending, arguing “it would be silly” to concluded the P2P promotes merchandise or ticket sales.

While there have since been responses from the American Assembly and further promotion of the NPD Group findings from the RIAA (along with coverage from CNET and TorrentFreak), no one seems to have picked up on the basic math error from NPD Group. The NPD Group post ironically starts with:

I often think you ought to have a license to publish data, especially these days, when misinterpreted statistics easily make their way to the blogosphere, and thus become truth.

Yet take a closer look at its own data in a chart that has been replicated throughout the blogosphere.