Government and law enforcement justifications for warrantless access to Internet subscriber information has long been defended on the grounds that the information being demanded carries little privacy interest. The go-to claim was always that it was “phone book information”, a reference to the largely discontinued practice of printing an annual public directory that included name, address, and phone number. The problem with that argument was that the information at issue included data points such as IP addresses and device identifiers, which could be used to track users and monitor online activity without a warrant. Moreover, linking a specific user to a specific IP address or other identifier effectively unlocks the door to potentially very sensitive information that is otherwise unavailable. Indeed, there is a reason that law enforcement logged over a million warrantless requests per year for basic subscriber information prior to the Supreme Court shutting down the practice.

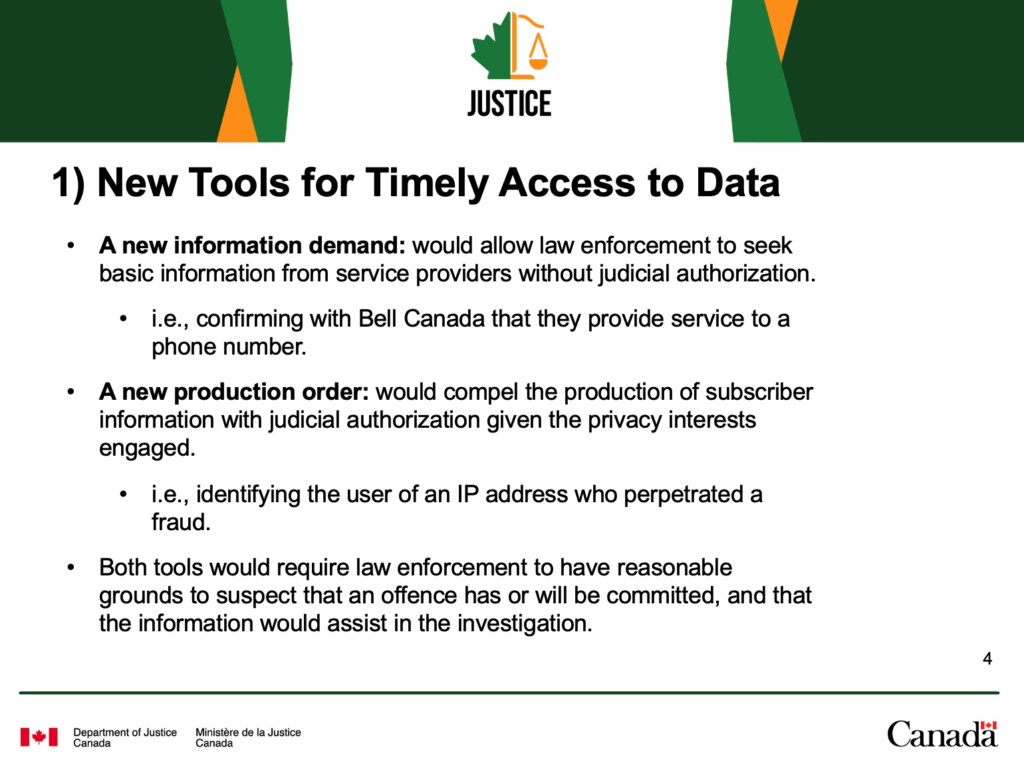

While Supreme Court of Canada rulings that there is a reasonable expectation of privacy with both basic subscriber information and IP addresses ended the warrantless access requests, the government is seeking to bring them back by burying a new “information demand” power in Bill C-2, the border safety bill. The government’s justifications for the change rely on old standbys such as protecting children, battling organized crime, and (now) combatting fentanyl. Yet it is notable that the government is also running back the claim that this is nothing more than phone book data. In a Department of Justice technical briefing document, the government claims that the information demand power would “allow law enforcement to seek basic information from service providers without judicial authorization.”. The example provided is “confirming with Bell Canada that they provide service to a phone number.”

Department of Justice Bill C-2 Technical Briefing Deck, page 4

This framing is incredibly misleading and vulnerable to legal challenge. The information demand power actually includes whether the person provides or has provided services to any subscriber or client, or to any account or identifier. This means law enforcement can start with a name, an IP address, or any other unique identifier attached to a phone in order to confirm service. For example, an IMSI catcher could be used gather phone identifiers at a protest and those identifiers could be used to confirm who provided the cellular service.

But that would only be the start. The information demand also includes the power to demand whether there is transmission data on hand (who was the person communicating with and what apps were they using) as well as where and when was the service provided (were they at the protest). The information demand can also cover when service began, when it ended, and what other communications services are used by the subscriber (do they use Gmail or WhatsApp). The specific content would require a warrant, but all of this data, which can be very revealing, would be available without judicial oversight.

Moreover, law enforcement need only “reasonable grounds to suspect” that an offence has been or will be committed. An offence in this case is not limited to the Criminal Code, but rather covers any Act of Parliament so this extends far beyond criminal investigations. In the case of CSIS, even the reasonable grounds to suspect standard is not needed as there is no requirement for any reasonable grounds. Bill C-2 simply gives the right to demand this information for any reason at all.

The privacy implications associated with the warrantless information demand power are obvious and cannot credibly be dismissed as mere “phone book” information. Law enforcement may have good reason to want this information, but given the privacy risks, there is a need for judicial oversight and authorization. The Supreme Court has been clear on the issue and the government’s attempt to circumvent constitutionally based privacy safeguards with misleading claims should be firmly rejected.

Pingback: O que é Invoice C-2 e isso afeta você? - Manolada da Força

Pingback: Qu’est-ce que le projet de loi C-2 et cela vous affecte-t-il? – Les Actualites