The federal government’s plans to regulate internet streaming services such as Netflix and Spotify through the Online Streaming Act have been mired in regulatory battles and court cases for many months. My Globe and Mail op-ed notes that the government’s plans finally took a small step forward last month, as Canada’s broadcast regulator, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, completed weeks of hearings into what counts as Canadian content, or “Cancon.”

Yet in the midst of the latest hearings, the Quebec government threw a monkey wrench into the entire process. Not content to wait for the CRTC process to play out, the provincial government introduced its own streaming regulation bill that is likely to spark a constitutional challenge. Quebec’s Bill 109 contemplates government intervention into how content is presented to subscribers, and would introduce unprecedented quota requirements that could lead to blocked services in Quebec or the removal of thousands of non-French titles from content libraries.

Matthew Lacombe, Quebec’s Culture and Communications Minister, framed the bill as a constitutionally valid initiative designed to increase consumer awareness of French-language content on global streaming services. However, the constitutionality of the legislation is anything but certain. The Supreme Court of Canada has repeatedly ruled that the power to regulate broadcasting falls to the federal government. The key question is whether internet streaming constitutes broadcasting.

If the answer is yes, the federal law would apply, and the Quebec bill faces the prospect of being declared unconstitutional. Alternatively, if internet streaming is not broadcasting – and some have argued that it is not – then the federal law may be declared unconstitutional, but the Quebec bill would stand. Either way, it is difficult to square how the federal and provincial efforts to regulate online streaming can legally co-exist.

Leaving aside the constitutional vulnerabilities, the Quebec bill appears to be a solution in search of a problem. For example, it envisions creating new regulations to increase the “discoverability” of French-language content (the bill notably refers to French-language content, not Quebec-based content). The CRTC is thinking of similar measures, but the truth is that streaming services have no interest in hiding the content their subscribers want to see. As subscription-based services subject to cancellation at any time, the incentives are precisely the opposite, since subscriber retention is directly linked to presenting a steady stream of content that interests.

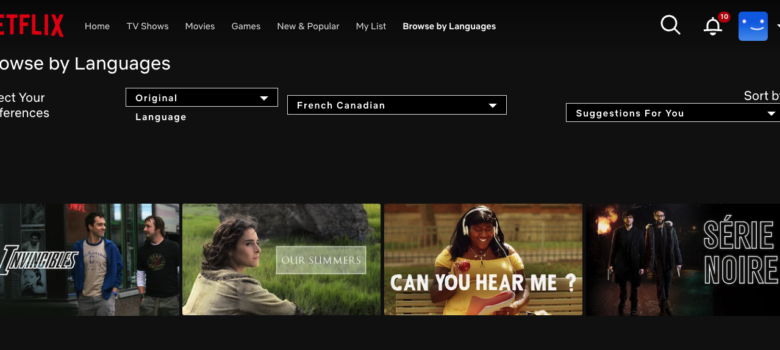

If the goal is simply to ensure that French-language content is readily available, the services already do so. On Netflix, “browse by language” is one of the top customization choices on the main page, with both French and French Canadian listed as options. On Amazon Prime, users can select up to five languages for recommendations.

The most problematic aspect of the bill may lie in its emphasis on quotas, which would establish regulations mandating that a certain percentage of the content library of streaming services be in French. The government hasn’t said what percentage will be required – it is leaving the specifics to future regulation – but the use of a quota system is almost guaranteed to lead to content removal for Quebec-based subscribers.

Indeed, one possibility is that international streaming services may exit the Quebec market altogether. With many objecting to the increased regulatory costs resulting from the federal legislation, an additional layer of provincial regulatory costs in the form of new licensing fees to meet the quota requirements may simply tip the scales and render the market more trouble than it is worth.

Alternatively, the services may seek to meet the quotas by removing non-French-language content. Assuming the regulations require a certain percentage of French language content – say, 30 per cent of Netflix’s content library – that will be met primarily by removing English-language and other non-French content to reach the mandated percentage. Content removal will mean less choice for Quebec-based subscribers without any requirements for more Quebec content.

The situation is even more challenging for non-video streaming services. How does a service such as Spotify – which allows anyone to upload their content on the audio service – comply with quota requirements? Podcasts are also captured by the bill, raising similar questions about how a podcast platform can effectively comply with French-language quotas.

Should the bill prove unworkable, it envisions an out by allowing the government to negotiate settlements directly with the platforms. That approach is eerily reminiscent of the federal Online News Act, which has resulted in blocked news links on Facebook and Instagram for nearly two years. The Online Streaming Act has its faults, but creating multiple, conflicting streaming regulation laws led by Quebec’s Bill 109 is far worse.

And how does the streamer determine if the law is applicable? I live in Ontario, just outside of Ottawa. My internet access is via satellite, so when I go to e-commerce sites such as Home Depot, etc, my location information is suspect at best; I just did it and it detected me as closest to the Pembroke, ON store whereas Carleton Place is closer, as is all of the stores in Ottawa, Renfrew, etc.

What I find offensive about Bills like this is that they basically say that “You’re not consuming enough of the content we want you to, so we will shove it down your throats and make you pay for it.”

I believe that streaming sites using geolocation to present residents of Quebec with a choice of just one (1) recording in French that explains that this bill/law is the reason for the rest of the library not being available to them will be in full compliance.

Pingback: Quebec’s Streaming Bill Could Kill Your Netflix Library | iPhone in Canada

Pingback: Navigating Quebec's Streaming Regulations and Canadian Culture

Reading the analysis of Quebec’s streaming regulation bill, I’m concerned it might complicate streaming services and even reduce content options for us.

If this bill is truly unconstitutional and unworkable, wouldn’t its implementation cause a lot of problems? It seems problematic.

Since streaming services already offer French content recommendations, is this new bill really necessary? It feels a bit redundant.

Michael Geist’s analysis is spot on; creating so many conflicting streaming regulations really does more harm than good.

I just hope these regulations don’t end up affecting my ability to watch shows normally; being able to easily find what I want to watch is most important.