It has been nearly two months since the Supreme Court of Canada issued its landmark five copyright decisions. In the aftermath of those decisions that provided a strong defense of users’ rights and fair dealing, I have written multiple posts on the implications for education and Access Copyright. These include […]

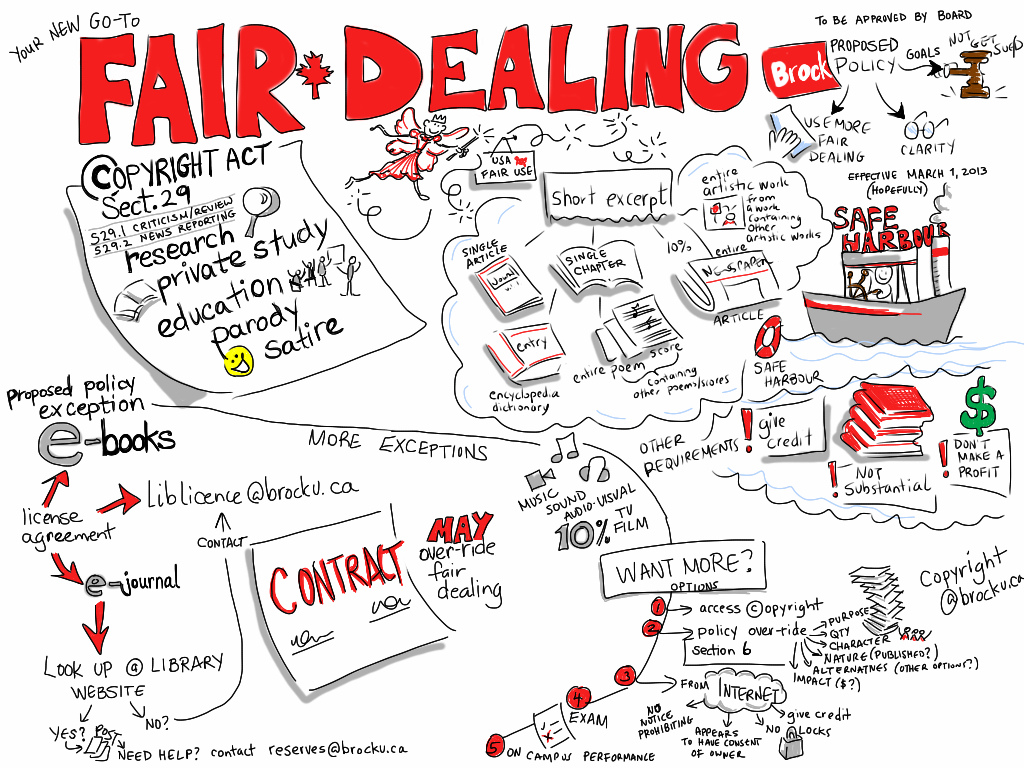

Fair Dealing by Giulia Forsythe (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) https://flic.kr/p/dRkXwP

Copyright

The Economist on Canadian Copyright Law

The Economist focuses on new copyright rules for the digital age, rightly pointing to Bill C-11 as “setting a new standard of permissiveness” (though it neglects to mention the restrictive digital lock rules).

The Supreme Court of Canada Speaks: How To Assess Fair Dealing for Education

I’ve posted several pieces on these issues (fair use in Canada, technological neutrality, impact on Access Copyright), but given the ongoing efforts to mislead and downplay the implications of the decisions, this long post pulls together the Supreme Court’s own language on how to assess fair dealing. The quotes come directly from the three major fair dealing decisions: CCH Canadian, Access Copyright, and SOCAN v. Bell Canada.

Note that this post is limited to the Court’s decisions and does not focus on the changes in Bill C-11. The legislative reforms provide additional support for education as they include the expansion of fair dealing to include education as a purposes category, a cap of $5000 on statutory damages for all non-commercial infringement, a non-commercial user generated content provision, an education exception for publicly available on the Internet, a new exception for public performances in schools, and a technology-neutral approach for the reproduction of materials for display purposes that may apply both offline and online.

Why the End of Access Copyright K-12 Licensing for Is Not The End of Payment for Educational Copying

In light of the decisions and recent copyright law reforms, K-12 schools are likely to conclude that they do not need an Access Copyright licence. While the collective and its supporters will react by claiming that this will greatly harm Canadian publishers and authors, the reality is that schools have permission to reproduce the overwhelming majority of materials without Access Copyright or fair dealing.

Access Copyright has argued that the case only focused on 7% of copies, but the truth is that it involved an even smaller amount. The 7% figure stems from the copies for which Access Copyright seeks payment. In fact, the Access Copyright sponsored study that lies at the heart of the K-12 case found that schools already had permission to reproduce 88% of all books, periodicals, and newspapers without even conducting a copyright analysis or turning to the Access Copyright licence.

How the Supreme Court of Canada Doubled Down on Users’ Rights in Copyright

The shift began in 2002 with the Theberge decision, in which Justice Binnie for the majority discussed the copyright balance: