My latest Globe and Mail op-ed begins by noting that digital sovereignty has emerged as the watchword driving Canada’s digital policy agenda, as the government seeks to position the country as a global leader in artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies. The increased emphasis on digital policy is welcome given the years of neglect or failed strategies that yielded little more than court challenges, trade disputes and blocked news links. Yet the focus on infrastructure spending as the key catalyst for addressing digital sovereignty risks is misplaced and unlikely to safeguard against lost autonomy and control.

The appeal of investing billions in government-supported digital infrastructure with the promise of “sovereign AI” is easy to see. Companies line up to get their share of public funding for capital investment they would have made anyway, governments invariably find it easier to cut cheques than usher complex legislation through Parliament, and the public can visualize tangible technology infrastructure situated on Canadian soil.

While there are certainly benefits to fostering a more competitive market with homegrown cloud provider alternatives, the reality is that the location of the infrastructure provides little assurance that domestic law and policy will apply to Canadian data or that the risks of foreign influence over network activities will be significantly reduced.

The infrastructure investments may sound big, but they pale in comparison with global capital investment in AI. The result is a relatively small Canadian footprint that will leave many reliant on foreign compute capacity for years to come. Moreover, the cybersecurity risks that accompany the infrastructure deployment are real, requiring investment and technical sophistication that most smaller players can’t realistically bring to the table.

Canada’s larger telecom companies may be better positioned to address those concerns, but they face much the same legal risk that comes with relying on U.S. giants such as Google, Amazon, and Microsoft.

Those companies are loath to promote it, but data sovereignty requires more than hosting the data in Canada or ensuring it is controlled by Canadian companies. In fact, the Treasury Board recently acknowledged in a government white paper on digital sovereignty that “using a Canadian supplier or storing data in Canada does not guarantee data will be outside the jurisdiction of foreign courts.”

The key question over the application of U.S. laws such as the CLOUD Act (which grants the power to compel disclosure of data anywhere in the world) turns on whether the company possessing the data has sufficient links to the U.S. such that a court could comfortably issue a binding order compelling data disclosure.

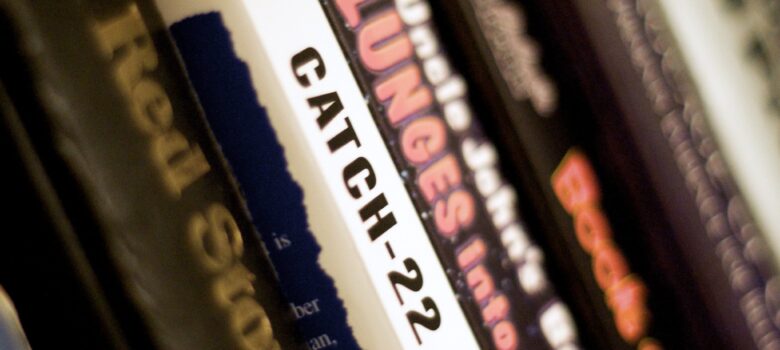

Canada’s digital sovereignty catch-22 is that smaller companies might be positioned to skirt the U.S. presence risk but lack the resources to develop a truly robust sovereign competitor. Conversely, the larger companies might be able to build viable alternatives (albeit on a smaller scale), but their deep links to the U.S. mean they are as vulnerable to a U.S. court order as their Silicon Valley-based competitors.

The U.S. is hardly alone in asserting jurisdiction over global data in this way, as recent reports indicate that Canada has done the same. Earlier this year, the RCMP sought disclosure of data held by OVHcloud, a French-based cloud provider. That demand was upheld by a Canadian judge, which similarly relied on the foreign company’s presence in Canada to issue the necessary court order.

Canadian-based infrastructure has its advantages, but digital sovereignty isn’t one of them. Solving that issue starts with legal solutions that modernize Canadian privacy and data governance laws. This has two obvious benefits. First, our woefully outdated laws pre-date today’s social media and AI companies, meaning we desperately need rules, penalties and enforcement powers that are better able to counter today’s privacy risks. Indeed, our weak laws beg the question of why Canadians are so anxious to ensure Canadian law applies to their data when the law itself does a poor job of providing effective protection.

Second, the primary counter to a potential foreign court order is demonstrating that the legal conflict – U.S law demanding disclosure versus Canadian law seeking to stop it – would result in serious penalties to the company stuck in the middle. That could turn Canada’s law into a “blocking statute” that might persuade a court to limit the scope of its order. Such an approach would do far more than point to Canadian-based cloud infrastructure to demonstrate that we take our privacy and digital sovereignty seriously.

It would make great sense for Canada to team up with Europe. Digital sovereignty does not carry a nationalist notion. The European Commission presented promising cloud sovereignty criteria.

Looking to add a unique touch to your space? A 3d wall printing machine can print any design directly onto your wall!

The application of wall printers is revolutionizing industries like advertising, interior design, and education by offering cost-effective, customizable solutions for large-scale wall art.

Grinding for hill climb racing 2 coins feels easier when you discover helpful tips like these. Great share for gamers.

I park my car in busy London streets, and I’ve had my upholstery fade and get damaged from the sun before. This time, I decided to try window films, and I’m so glad I did. The difference is night and day — my seats and interior no longer show signs of sun damage. I’ve been to a few places in the past, but this company’s professionalism and clear communication were top-notch. Their film really https://www.tintfit.com/ does what it promises, and they walked me through everything, making sure I was fully informed from start to finish.