Later this week, a government appointed panel tasked with reviewing Canada’s broadcast and telecommunications laws is likely to recommend new regulations for internet streaming companies such as Netflix, Disney, and Amazon that will include mandated contributions to support Canadian film and television production. In fact, even if the panel stops short of that approach, Canadian Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault and Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission chair Ian Scott have both signalled their support for new rules with Mr. Guilbeault recently promising legislation by year-end and Mr. Scott calling it inevitable.

My Globe and Mail op-ed notes that the new internet regulations are popular among cultural lobby groups, but their need rests on a shaky policy foundation as many concerns with the fast-evolving sector have proved unfounded.

Supporting the “System”

Canada implemented mandated contributions to support the creation of Canadian content years ago, maintaining that broadcasters and broadcast distributors such as cable and satellite companies benefit from the “system” and therefore should be required to contribute back to it.

The system does indeed provide broadcasters and broadcast distributors with many regulatory advantages. These include lucrative simultaneous substitution rules that allow them to replace U.S. commercials with Canadian ones, foreign investment restrictions that limit competition, must-carry regulations that mandate that certain channels be purchased by consumers in even basic cable packages, copyright rules that legalize redistribution of broadcast signals, and protection to keep U.S. giants such as ESPN and HBO out of the market.

That is the Canadian “system” and, given the benefits, mandated contributions are best viewed as a regulatory quid pro quo.

Internet-based streaming services are not beholden to this system, however. Notwithstanding calls for a “level playing field”, they do not enjoy any of the Canadian broadcast regulatory advantages. Simply put, there is no free ride. Rather, Canadian and foreign streaming services are equally subject to lightweight regulations, reflecting a business model that depends upon on winning consumer choice rather than regulatory favour.

Saving the Canadian Production Sector?

Supporters of internet regulations have also argued the Canadian film and television sector will be decimated if mandated contributions are not applied to the streaming services. The argument is a simple one: the broadcast and broadcasting distribution sectors are in decline and the burden of support should therefore shift to the internet.

However, the data confirms fears about the Canadian film and television sector have been overblown with record setting production in Canada. The total value of the Canadian film and television production has nearly reached $9 billion annually, a record with overall production increasing in 2018 by 5.9 per cent. Canadian content has enjoyed remarkable success as well with the past two years setting the high water mark for the prior decade.

In the words of the CRTC’s Mr. Scott, Netflix is “probably the biggest single contributor to the [Canadian] production sector today.” The company committed in 2017 to spend at least $500 million over five years on film and television production in Canada but has already exceeded that figure.

What Makes a Program “Canadian”?

Given the massive foreign investments in Canada, cultural groups are now concerned there is too much of a good thing, resulting in an expensive production environment that may favour foreign location and service production and crowd out “Canadian” content. But if this is the basis for mandated contributions and content requirements, it too rests on a weak foundation.

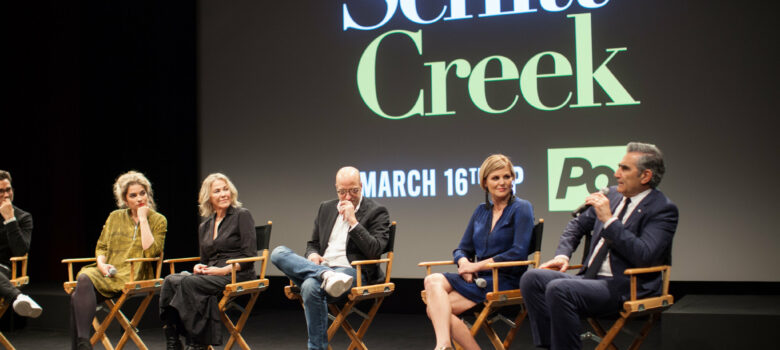

First, global streaming companies have proved exceptionally successful at exporting Canadian content to the world. Programs such as Schitt’s Creek attract a loyal domestic viewership, but it took Netflix to extend its reach to a global audience.

Second, Canadian content is not hard to find on streaming services. Searching for it is easy and smart algorithms quickly learn to recommend more of the same if that is a subscriber’s preferred viewing choice.

Third, the not-so-secret reality of the Canadian system is that foreign location and service production and Canadian content are frequently indistinguishable. Qualifying as Canadian requires having a Canadian producer along with meeting a strict point system that rewards granting roles such as the director, screenwriter, lead actors, and music composer to Canadians.

Yet this is a poor proxy for “telling our stories”. The rules mean foreign companies can never produce Canadian content leading to the absurd outcome that revivals of Canadian programs such as Trailer Park Boys and Degrassi will not meet the qualification requirements if Netflix is the sole funder and producer. Moreover, programs such as The Handmaid’s Tale may be based on a Margaret Atwood novel, but using one of Canada’s best known novelists as the source doesn’t count in the Canadian points system.

So what is Canadian? A quick scan of Canadian Audio-Visual Certification Office data turns up Blood and Fury: America’s Civil War, The Kennedys, Murder in Paradise, Natural Born Outlaws, Who Killed Ghandi?, and dozens of other programs that are Canadian in regulation-only. Further, there are also “co-productions”, in which treaty agreements deem predominantly foreign productions such as The Borgias or Vikings as Canadian.

Regulating in the Internet Age

Crafting a new regulatory framework based on this system does little to preserve or promote Canadian culture. If Mr. Guilbeault is serious about supporting Canadian content, a good starting point would be to overhaul the points system to better identify Canadian stories and cultural content.

Further, the government must recognize that Canadian law has long treated broadcasting as a scarce resource with an extensive licensing approach. Those privileged to be part of the “system” supported it because they benefited directly from its existence. However, the world of broadcast scarcity has given way to abundance in which anyone can broadcast their videos, podcasts or other content to a global audience without a licence.

Should the government regulate those providers and creators, it will be engaging in perhaps the most extensive speech regulation Canada has ever seen on the demonstrably false premise that doing so will level the playing field, support Canadian stories, or save a production sector that is thriving in the internet age.

Pingback: News of the Week; January 29, 2020 – Communications Law at Allard Hall