The Federal Court of Appeal’s ruling on Canada’s anti-spam law puts to rest persistent claims that the law is unconstitutional. As discussed at length in my earlier post, the court firmly rejected the constitutional arguments in finding that the law addresses a real problem and has proven beneficial. The impact of the decision extends beyond just affirming that CASL is (subject to a potential appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada) here to stay. It also provides important guidance on how to interpret the law with analysis of the business-to-business exception, implied consent, and what constitutes a valid unsubscribe mechanism.

The case itself involved commercial electronic messages sent by CompuFinder, a Quebec-based company that was promoting educational and training services in the emails. CompuFinder argued that the CRTC erred in its interpretation of the business-to-business exception found in CASL. The court notes that the exception includes three requirements:

This exemption applies where three conditions are met: (i) a CEM is sent by an employee of one organization to an employee of another organization; (ii) those organizations have a relationship; and (iii) the CEM concerns the activities of the receiving organization. The CRTC determined the appellant’s emails met neither the second nor third requirements for the exemption.

CompuFinder argued that there was a relationship since messages were sent to people at organizations that had previously purchased at least one training program. The CRTC found a small number of contracts with one or two employees was insufficient to meet the exception’s standard and the court agreed:

I see nothing clearly wrong with the CRTC’s determination that contractual relationships comprehending a very limited number of transactions affecting very few employees do not constitute relationships for the purposes of the business-to-business exemption.

The court added that there is a significant difference between a prior contractual relationship (which would permit sending commercial messages to the specific individual) and applying that relationship to an entire organization:

Finding an existing business relationship in the present case would permit the appellant to send CEMs to a person—an individual—who had paid the appellant for a course within the preceding two years. Finding a relationship for the purposes of the business-to-business exemption, on the other hand, would allow the appellant to send CEMs to not only the individual who took the course, or the individual who paid for the course, but to every other employee of the organization to which those individuals belong—and organizations can be very large indeed. The latter finding would expose a great many more people to the potentially harmful conduct that it is CASL’s raison d’être to regulate.

In other words, if I have a past contractual relationship, an organization can send me a commercial message, but not rely on the exception to send one to every employee at the University of Ottawa.

While the court was comfortable with a narrower approach to the relationship prong of the business-to-business exception, it did support a broad approach to defining “activities of the organization” indicating that it goes beyond core business operations:

Organizations engage in many activities that are not directly related to their core business operations and maintain relationships with other organizations to facilitate those supplementary activities. A communication pursuant to such a relationship is in no meaningful sense less of a ‘regular business communication’ than if the communication bore more directly on an organization’s core business operations. I find nothing in the text, context or purpose of the exemption that justifies reading-in qualifiers to circumscribe the vast universe of an organization’s potential business activities into a shortlist of ‘activities’ to which CEMs from partner organizations must relate in order for the business-to-business exemption to apply. I am therefore of the view that, where an organization pays for employee training courses – whether or not it is legally obligated to do so – the activities of that organization can include the purchase of employee training courses.

The court also considered the issue of conspicuous publication under the implied consent exception. CASL says that consent can be implied if the person to whom the message is sent has posted their address, not conspicuously published a statement that they do not wish to receive unsolicited commercial email, and the message is relevant to the business or role of the recipient. In this case, CompuFinder argued that it had the necessary implied consent. The CRTC rejected the argument, noting that some emails were taken from third party sites and that relying on job descriptions alone were insufficient to prove relevance. The court agreed:

organizations seeking to rely on paragraph 10(9)(b) of CASL would do well to be prepared to state explicitly the ‘business, role, functions or duties’ of recipient individuals or organizations – I do not believe the terms in quotations require further definition – at least insofar as it relates to the subject matter of the CEM in question. The organization should then be prepared to elucidate, equally explicitly, the relevance of the CEM to the recipient’s business, role, functions or duties thus stated. The express terms of paragraph 10(9)(b) of CASL, in my view, require no less.

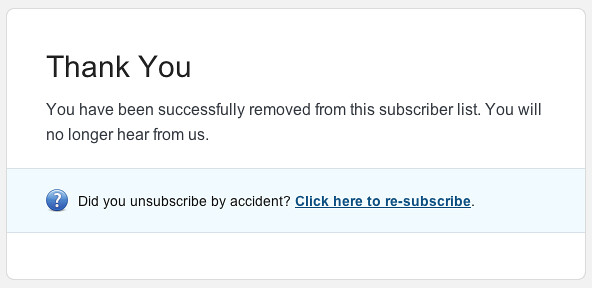

Finally, on the issue of a valid unsubscribe mechanism, CompuFinder’s emails often included two unsubscribe links – one working and one not. The CRTC ruled that this did not meet the necessary standard in CASL and the court agreed:

prior to selecting the functioning link, recipients are confronted with two alternatives with no clear indication as to which is the correct one to select. This, in itself, can cause delay and compromise the ease with which the mechanism is supposed to be accessible. These issues are compounded if the wrong mechanism is selected on the first attempt and recipients encounter an error message. It is not necessary to speculate whether this could create confusion and frustration among recipients – written statements from consumers seen by the CRTC confirm that it can, and has.

The case stands as the most important CASL case to date, providing both guidance on interpreting some of the provisions found in the law and strongly affirming that the law is constitutional.

Loves micheal geist pod casts

Pingback: ● NEWS ● #michaelgeist #canada #copyright #CASL #law ☞ What the Fed… | Dr. Roy Schestowitz (罗伊)

Pingback: ● NEWS ● #MichaelGeist #Politics ☞ What the Federal Court of Appeal… | Dr. Roy Schestowitz (罗伊)

Pingback: News of the Week; June 17, 2020 – Communications Law at Allard Hall