National Canadian Film Day 150, described as the world’s largest film festival, was held yesterday with events that showcased Canadian feature films at hundreds of venues from coast to coast. The event had a large number of sponsors (the Prime Minister promoted it) that helped place the spotlight on Canadian film. Yet a day devoted to Canadian feature film might also have called attention to the struggles of the Canadian feature film category and considered whether significant policy reforms are needed. This year’s Canadian Media Producers Association Profile 2016, which chronicles the industry (I used it earlier this year to discuss how foreign financing – not regulated contributions – is the now the top source of English-language television production in Canada), tells a story of a feature film industry that relies on public dollars to finance the majority of its costs, has hit a decade low in the number of films produced, and is experiencing declining budgets.

In the last reported year, the average English-language feature film budget declined to $2.2 million and the percentage of films with budgets over $10 million dropped to just 2%. There were a total of 94 feature films made, the lowest figure in the past decade. The average budget for a Canadian English-language fiction feature film was also its lowest in the past ten years.

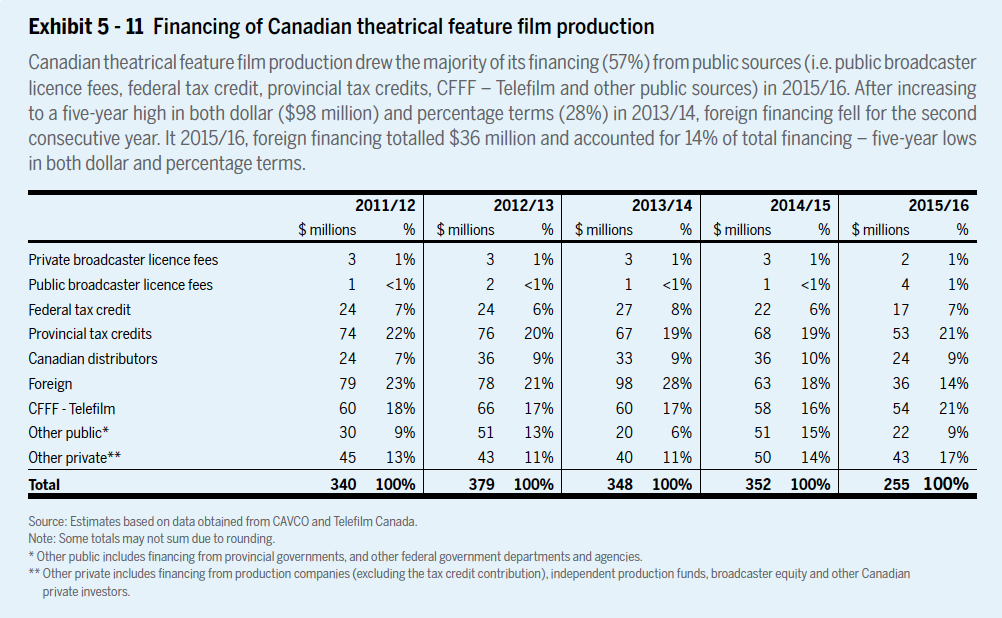

Funding for these films comes primarily from tax dollars with public sources accounting for $146 million or 57% of the total financing of Canadian theatrical feature film production. The total budget is small: $178 million for English-language films and $76 million for French-language films. The chart below highlights how little Canadian private sources spend on making feature films. After accounting for public dollars through CFFF-Telefilm, tax credits, and foreign money, less than one-third of funding comes from Canadian private sources. Note that this data is focused on Canadian feature film production to the theatres and does not include co-productions with other countries, which add an additional 26 productions (11 in English and 15 in French) with larger average budgets.

CMPA Profile 2016, Page 67, http://www.cmpa.ca/sites/default/files/documents/industry-information/profile/Profile%202016%20EN.pdf

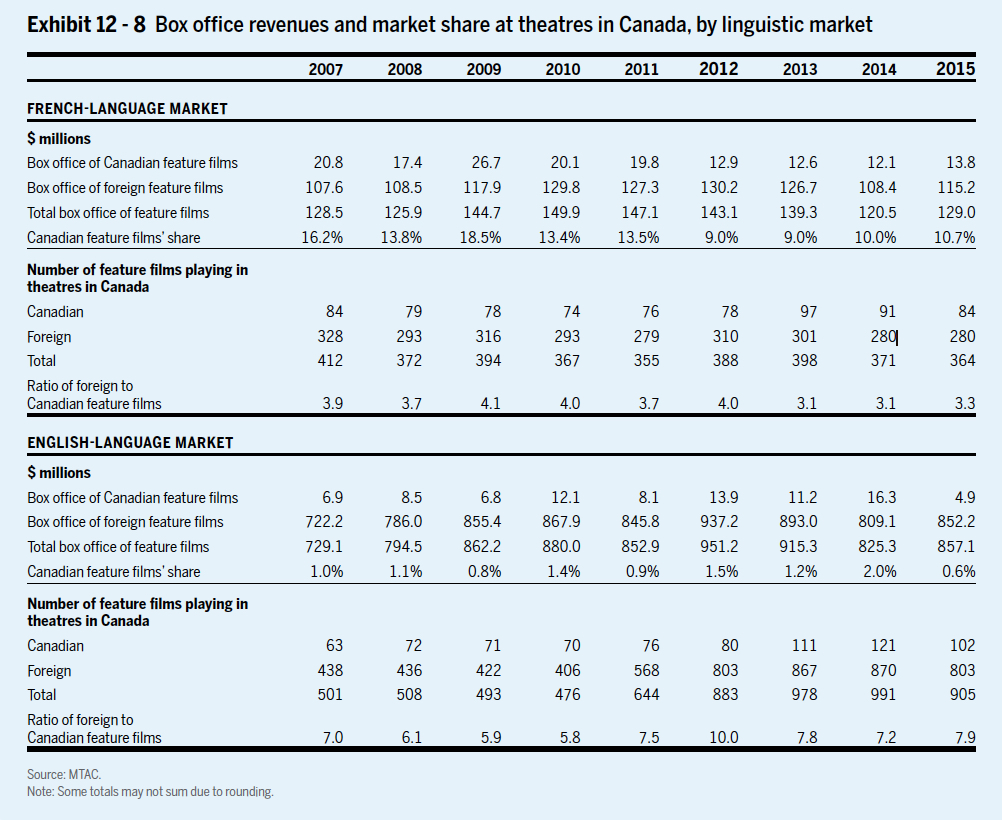

The audience for Canadian feature films isn’t great either. While going to the movies is a billion dollar industry in Canada, Canadian feature films garnered just 0.6% of box office receipts in the English-language market (the number is better in French at 10.7%). The revenues are truly tiny: a total of $4.9 million in revenue for English-language feature films out of a box office of $857.1 million. The low revenue is notable since there were over 100 Canadian films shown constituting 7.9 percent of all English-language films.

CMPA Profile 2016, Page 118, http://www.cmpa.ca/sites/default/files/documents/industry-information/profile/Profile%202016%20EN.pdf

There are surely many factors behind the performance, not the least of which is the popularity of U.S. films, which typically have bigger budgets and more promotion associated with them. But if Canada deems feature film important, is willing to spend millions in tax dollars and credits to support the industry, and wants to ensure that Canadian stories make it onto the big screen, then considering other policy issues is needed (Simon Houpt did so in an excellent piece in 2015).

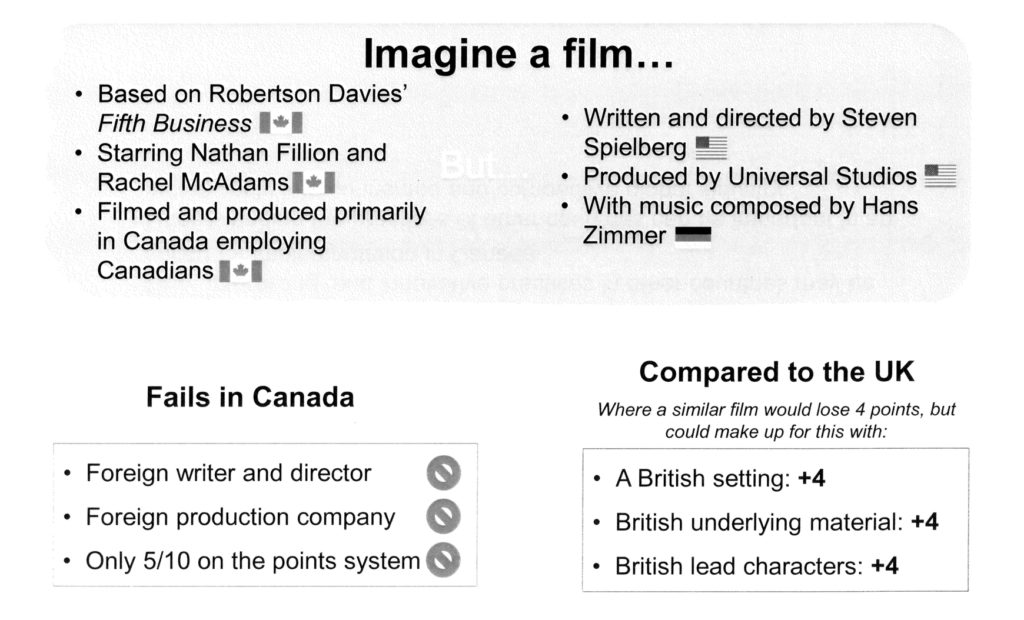

Topping the list of considerations might be how Canada defines a “Canadian film.” This issue was the subject of debate at the annual CMPA conference in February that was also covered by Houpt. While the debate and Houpt piece focus on the virtues and problems with Canadian 10-point system for determining whether a film qualifies as “Canadian”, the reality is that the Canadian approach is an outlier when compared with many other countries.

I recently obtained a study conducted by the Department of Canadian Heritage under the Access to Information Act that compared approaches in ten countries: Canada, Australia, the UK, Ireland, Hungary, New Zealand, Mexico, Germany, France, and Colombia. The study noted that point systems are common, but Canada stands alone in focusing exclusively on the nationality of personnel involved in the production.

The majority of countries allow for points for three main criteria: cultural content (the cultural contribution of the film itself), production (the degree to which the film is nationally produced), and personnel. Some countries emphasize one criteria more than another, but only Canada considers a film to be Canadian based strictly on the nationality of personnel. Canada is also the only country to require the company to maintain worldwide copyright.

The report notes that Canada’s focus on process may come at the expense of cultural outcomes:

In its pursuit of cultural goals, Canada maintains a distinct focus on a process rather than outcome based approach relative to other countries being examined. The Canadian system focuses solely on ensuring the creators behind the production are Canadian. Not only do other countries have lower requirements relating to the number of key staff that must have their countries’ nationality, they also allow low scores in this category to be compensated by strong scores in cultural content and production…

When trying to achieve cultural goals, focusing on outcomes rather than process has potential advantages and disadvantages. Traditional policy literature encourages focusing on outcomes, as this is the clearest way to connect policies to the mandate of government. For example, a film made entirely by Canadian producers and key creative staff could still be based on American source material, be set in the United States, and consist only of American characters. This would not necessarily be achieving the goals of producing distinctly Canadian cultural content.

An internal presentation that accompanied the report highlighted the limitations of the Canadian approach, noting a film based on a Canadian novel, starring Canadian actors, and filmed and produced in Canada might still not qualify as Canadian if written, directed, and produced by an American.

Canadian Heritage Slide Presentation, obtained under ATIP

The outlier cultural approach – when combined with the financial struggles of the Canadian feature film industry and the significant public investment in the sector – suggests that it is time to reconsider the Canadian system. The Canadian industry is enormously successful once foreign location and service production is taken into account. That side of the industry – in which foreign producers use Canadian locations for filming and services – was a $2.6 billion industry with 128 feature films last year. However, the industry often cites the cultural importance of Canadian feature films, in part to justify the significant public support. If the goal of the feature film industry in Canada is primarily cultural with box office success or film budgets deemed secondary, then changing the way we measure what constitutes a “Canadian film” is long overdue.

To begin, foreign financing is not the top source of revenue for Canadian English-language television production. It is second to provincial tax credits which are not regulated contributions (CMPA, Table 4.19)… But in any case, the foreign financing of Canadian television programs consists almost exclusively of pre-sales to foreign broadcasters and sales agents – not equity investment.

Simon Houpt’s excellent article does not really delve into alternative policy options. Nowhere in his article does he discuss the 10-point system.

It is completely false to say that Canada focuses exclusively on the nationality of personnel involved in the production. As the Canadian Heritage study makes clear on its first page, “Canada only considers personnel in its points system, but includes other factors in its eligibility criteria.” For a certified Canadian production, the production company must also be a qualified corporation as defined in the Income Tax Act. Not less than 75% of the total of all costs incurred for the post-production must be incurred for services provided in Canada. The production company must control the initial worldwide exploitation rights over the production. There must be confirmation in writing from a Canadian distributor or a CRTC-licensed broadcaster that the production will be shown in Canada within the two-year period following its completion. The production company or a related taxable Canadian corporation must retain an acceptable share of revenues from the exploitation of the production in non-Canadian markets. ETC. None of these requirements is related to the nationality of the personnel.

The production company must be the exclusive worldwide copyright owner – but this may be alone, with one or more domestic co-producers, or jointly with other prescribed persons.

“When trying to achieve cultural goals, focusing on outcomes rather than process has potential advantages and disadvantages. Traditional policy literature encourages focusing on outcomes, as this is the clearest way to connect policies to the mandate of government. For example, a film made entirely by Canadian producers and key creative staff could still be based on American source material, be set in the United States, and consist only of American characters.”

The study from which this quote is taken concerns certification for federal tax credit purposes only. It does not concern the rules that determine Telefilm Canada or provincial government financing. The Canadian point system is a relatively objective approach to the certification of Canadian content which has the advantage of using quantitative measures. This quantitative approach does not involve the analysis of scripts or program content that is associated with a subjective or discretionary approach that can lead to bad decisions and censorship. Administration of the CAVCO approach does not require sophisticated analysis and is generally not disputed. Focusing on “outcomes” is what Telefilm Canada does…

There have been many films based on Canadian novels that did not qualify as Canadian content, and rightly so. Never Cry Wolf was based on a Canadian autobiography (Farley Mowat) and shot partly in Canada. First Blood (the first in the Rambo series) was based on a Canadian novel (David Morrell), directed by a Canadian (Ted Kotcheff) and shot in British Columbia. The English Patient was based on a Canadian novel (Michal Ondaatje) and featured at least two Canadian characters (played by French and American actors). As good as all of these films were, none could be considered Canadian audiovisual content.

The problems of the Canadian feature film industry have been debated for at least 50 years. Solutions that appear to work on the French-language side in Québec, at times, are not always transferable to the English-language side. Success and failure are largely the result of a crap shoot in which the odds are very small. This is true all over the world. Unfortunately, The Reel Story makes no contribution to the discussion of what is to be done to improve English-language film development, production, distribution and exhibition…