The Globe and Mail’s Simon Houpt ran a column over the weekend titled It’s Time to be Honest: Netflix is Parasitic. The piece received some positive commentary on Twitter, with some suggesting that it provided a counter-view to the Netflix support that has prevailed publicly and politically for several weeks in Canada. Houpt uses some effective imagery (Netflix as a Wal-Mart or Costco behemoth that will lay waste to Canadian film producers in the same way that the retail giants take out “mom and pop” stores), but this post argues that he does not come close to making his case.

The Netflix backlash (also found in Globe pieces from Kate Taylor and John Doyle) can be distilled down to two key concerns. First, that Netflix only produces a limited amount of original content and merely selling access to a large library will gradually mean no new content. Second, that Netflix (unlike the conventional broadcasters) does not contribute to the creation of original Canadian programming and the erosion of that support will lead to the end of new Canadian content. This second concern lies at the heart of the calls for a mandatory contribution by Netflix (referred to by some as a Netflix tax).

I address each of these concerns below, but start by noting that though Netflix is the current market leader, there is every reason to believe that there will be other major players in the video streaming market. In the U.S., Hulu and Amazon Prime already offer large libraries of content, while Showmi (from Rogers and Shaw) is set to launch in Canada later this fall. While some of the online video services are tethered to a cable or satellite subscription, true independent online video services should continue to grow and so long as they offer good value for money, consumers may subscribe to more than one service. This suggests a competitive online video market that competes for both subscribers and content.

That competition is the reason that online streaming services are likely to increase the amount of original content created, not decrease it. Companies like Netflix are funding their own original content (House of Cards, Orange is the New Black) and extending older series that started on conventional television (Arrested Development, Trailer Park Boys), but the bigger source of revenue for new series is that streaming video services will compete for the right to add them to their libraries for streaming purposes. Streaming rights are reportedly selling for as much as $750,000 per episode for top shows, with executives describing it as the “defacto domestic syndication window.”

In other words, shows that might have previously been cancelled or not made due to financial concerns (particularly that the show might not make it to syndication, which often represents a major source of revenue), are now relying on streaming revenue to provide a guaranteed source of income. In fact, this article shows how a combination of streaming revenues, tax breaks, and international sales covered the full production cost of a $3 million per episode show without any advertising revenues. This experience is not limited to U.S. shows. The same article points to Vikings, a Canadian-Irish production that generated significant revenues from streaming deals in Germany and the U.K. The opportunities presented by streaming revenues should excite television producers because there is the potential for a broader array of content (the limits imposed by a broadcaster’s need to fill a schedule are gone) and public interest will be invariably linked to commercial success (make stuff people want to see and streaming companies will pay).

Even with some Canadian success stories, however, critics will still argue that without financial contributions toward the creation of Canadian content from companies like Netflix, Canadian content will disappear, leaving nothing to license to streaming companies. Yet a closer look at the numbers suggests that Canadian productions will continue with or without a Netflix contribution. The data shows that the Netflix contribution would be insignificant relative to the existing financing of Canadian productions. In fact, the largest single source of financing remains the public, which pays for the creation of Canadian content through tax credits and direct government contributions.

Houpt says that Netflix generates $300 million per year from Canadians. Leaving aside the objections to a Netflix tax (online video is not broadcasting, jurisdictional questions about links to Canada, Netflix being unable to benefit from the contribution), assume that online video services are required to contribute at the same five percent rate as the regulated industry. The $300 million in revenue amounts to a $15 million contribution from Netflix.

Would $15 million alter the economics of the Canadian television production industry?

Not even close.

The Canadian Media Fund, the recipient of the contributions, reports revenues of $365 million in its last financial statement (roughly 2/3 from the industry contributions and 1/3 from the government). In other words, the Netflix contribution would be roughly 4 percent of CMF’s annual revenues. That is pretty minor, but CMF itself is only a small part of the overall source of funding for Canadian productions.

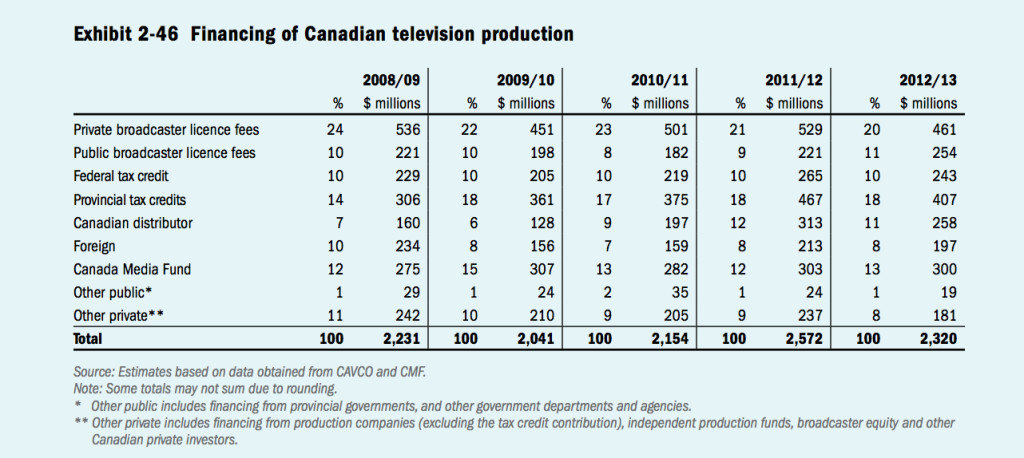

The Canadian Media Production Association provides detailed data on the industry in annual economic report. The latest report indicates that spending on Canadian television production amounted to $2.32 billion in its latest year. As the chart below notes, the CMF funding constituted 13% of the total financial cost. Far more important sources of funding come from broadcaster licence fees and the public in the form of federal and provincial tax credits. In fact, the combination of tax credits and the government contribution to CMF means that the taxpayer remains the largest source of financing for Canadian productions.

CMPA, Profile 2013, http://www.cmpa.ca/sites/default/files/documents/industry-information/profile/Profile2013Eng.pdf

Taken together, a Netflix contribution of $15 million is only 4% of CMF funding, which itself amounts to only 13% of total television production financing (and the broadcast distributor contribution is roughly 2/3 of the CMF funding or just over 8% of the total financing). The total value of the Netflix contribution to a $2.3 billion industry: 0.6 of 1%. Of course, that is only the “lost” financial contribution and does not factor in the benefits that come from Netflix funded productions (such as Trailer Park Boys) nor the increased value of productions that come from licensing streaming rights.

Yet somehow the absence of less than one percent of funding spells the end of Canadian productions and renders Netflix a “parasitic” enterprise? Hardly. Even if the market grows dramatically – perhaps tripling in size with Netflix and other foreign competitors generating a billion a year – the overall effect on lost contributions to Canadian productions will remain tiny relative to the total expenditures that come from public dollars, licensing fees, and investment from producers.

Houpt concludes by arguing that it is worth having a conversation about the future of television and broadcasting in Canada and the role of Netflix. I agree and would argue that the public outcry against the CRTC’s threat to impose new regulations on Netflix is part of that discussion as is the economic data that points to a multi-billion dollar industry that will not rise or fall based on handouts from online video services.

I like your piece here. Sorry, this will be a rant & likely jump around between TV & Internet because they are both related in this discussion. It really irks me that the CRTC is so corrupt. I think if you pay for a TV package, then there should be absolutely no commercials, otherwise, I have an antenna & enjoy TV from both the US & Canada for Free. I use Netflix & other services (like Amazon instant Video) to stream shows, movies & PPV. I also use the Sports services themselves (like UFC channel, NFL Sunday Ticket, etc… to watch the games & events I want). I have no problem paying for them, but WHY ON EARTH would I pay a ridiculous amount monthly for the privilege of watching commercials & having to pay (the same rate as non-subscribers for special events, PPV movies or specialty channels. I think VMEDIA has done an awesome job helping change the playing field, but to this day Bell & the others still use their dirty tactics (i.e. turning down 3rd party internet speeds randomly) to take customers back. The government should purchase all the FIbre lines from Bell in every major city across Canada (this was done in QC I believe) & then rent them to whomever & allow for truly open competition. Don’t even get me started on the ridiculous notion of increased internet speeds with the stupid bandwidth caps!

Keep up the good work Michael.

Every time something new comes along in the entertainment industry, a hue and cry has gone up that it will destroy some part of the business. It’s never happened.

Yes, industries changed but didn’t go away.

In the 1950s, the movie studios cried that free television would be the downfall of motion pictures. Why, it was argued, would anyone pay for a ticket when they can sit in their living room and be entertained by Milton Berle for free?

It never happened.

When Pat Weaver, once the head of NBC, proposed a pay TV service in the late 1950s, the networks and local stations alike claimed such a service would destroy broadcasting. The California legislature actually passed a bill prohibiting pay TV in the state.

Yet HBO and its imitators didn’t destroy broadcasting any more than broadcasting ruined the movie studios.

Musicians and singers once yowled that MP3 players would mean the end of the recording industry. But ticket and album sales have never been higher.

Now, television is whining that Netflix will destroy their business. It won’t happen. Television may change – again – in the face of new ways people are viewing programs; indeed, it is changing already as evidenced by the fact that networks and even program producers are making shows available on line. But whether or not Netflix contributes to the Canadian production fund, Made In Canada shows and movies will continue to be produced, people will watch them if the quality is good, and the industry will continue to thrive. Maybe not in its current form but in new and (hopefully) better ways.

Lemme see, what went by on the tube last night. holmes on homes, leave it to brian, pickers, and antique road show.

one us program. maybe two if that vulture locker show counts.

(I had rereated to the box already. Like my father, i spend a few hours a day reading the news.

and what is the vermin doing? (bigotry, delusions and ghettoizing) what this time?

Should also note that the $300 million Netflix collects also generates $18 million or so in tax….transactions which might not have otherwise occured. Far more than the $15 million a 5% unfair and unenforceable tax would collect.

The fact is the Canadian economy, government revenues and by extension all Canadians do derive some benefit by default.

And it’s true that Netflix is but one. Cineplex offers movies as does Sony while many people are happy watching Chromecast and YouTube channels.

Ian, for the sake of accuracy NetFlix does not generate, collect or remit any taxes. They made it very clear at the Lets Talk TV hearing that they have no employees or presence in Canada so they are not subject to any Canadian regulations or taxes. They acknowledged that their only contributions to Canada’s economy were the occasional use of Canadian dubbing services and they funded production of a couple episodes of Trailer Park Boys.

pretty sure I pay GST on my Netflix bill.

Nope, $7.99 a month, no taxes.

Description Unit price Qty Amount

$7.99 CAD 1 $7.99 CAD

Subtotal $7.99 CAD

Total $7.99 CAD

Payment $7.99 CAD

Invoice ID: 4428097198

This ignores the direct and indirect contributions that Netflix makes to the Canadian film industry already. Netflix carries a number of shows that were filmed (at least partially) in Canada. Two examples that I found quickly are Stargate: SG1 and Supernatural, both filmed in and around Vancouver. While these shows are/were primarily produced in the US, a large portion of the crew and (to a lesser extent) talent who worked on the shows are Canadian. While not directly funding new shows or films, it can cause future incentives for filming in Canada.

Beyond that, Netflix already pays for some shows that are fully filmed and produced in Canada. Being Erica and Republic of Doyle are two CBC shows currently on Netflix (I’m sure there’s more). Think about that for a second. Netflix is basically providing funds to our public broadcaster (through licensing deals), and nobody is forcing them to do that. Now I have no idea how many people are watching these shows in the US or overseas (or if they’re even available in the other markets), but does that really matter?

In the end, Netflix shouldn’t be forced to support current Canadian productions, because it’s already doing a pretty good job of supporting past productions. It’s also bound to happen that Netflix will directly support film production in Canada. Just like Vancouver (and Toronto, Montreal, and even little Chester, NS) are economically viable (even beneficial) locations to film in for the US broadcaster and cable companies, so too are they for the likes of Netflix. It would not surprise me to see Netflix start filming some of their original series in Canada. I doubt we’ll see that happen if the CRTC remains hostile, though.

Via Netflix, I’m watching a series called Once Apon A Time, and noted the majority of the filming took place in Steveston, Richmond, BC and other scenes taking place in the North Shore mountains. This is a series a friend said she watched a few years ago on cable tv. Streaming video services now allow me to appreciate it at my convenience, to support a production I enjoy. There are other Canadian stories I’d like to see again: Intelligence, Da Vinci’s Inquest, Radisson and R.C.M.P., and just maybe a streaming service like Netflix will do it.

I think Netflix could leverage original Canadian content production in a more effective manner. They have Canadian content from CBC as MBaedley mentioned, so maybe they’d do a better job at using viewing data to determine what new shows to produce. Maybe they’d make Canadian content that more Canadians would want to watch.

Don’t worry, CRTC… there’ll be remakes of Anne of Green Gables for many years to come.

I certainly don’t think the invasion of Netflix (or Netflix-like OTT) services is ever going to spell the *end* of Canadian television – but one area where I liked the Haupt analogy of Wal-mart is that it absolutely could control what Canadian television *looks like* (in the same way that Wal-mart didn’t mean the end of retail – but it did reshape the landscape so that only the largest bulk manufacturers of the most common commodities had a market any more).

Yes OTT services have started commissioning original series – but in very limited areas. In the past two years Netflix has commissioned 80 total episodes of dramatic (or comedy-drama) involving hollywood star or creative talent (House of Cards, Bad Samaritans, Hemlock Grove, Orange is the New Black), 20 total episodes of ulta-low budget animation (Bojack Horseman, The Problem Solverz), and 63 episodes of studio franchise spin offs, or shows notable for cult fanbases and lower than average production costs (Arrested Development, Trailer Park Boys, The Killing, Star Wars: Clone Wars, Turbo FAST).

The CBC (who I’m not holding up as any kind of paragon, but rather a troubled national broadcaster) will commission well over three times that amount of programming *this fall alone*.

There’s also never going to be an obvious OTT interest in subsidizing the types of programming that many people enjoy like news, sports (which has no replay value and is a loss leader for most networks), educational programming and the like – so the increased involvement of OTT networks absolutely potentially changes the character of what’s available on television.

I understand that most people don’t like 99% of what’s on regular broadcast / cable (and I’m one of you) but at least that’s an ecosystem that can support diversity of programming because everything on there is *someone’s* favorite show.

As to the argument about streaming revenue, it’s true that revenues are slowly starting to come up – but only for American studios which can package multiple properties into mega-libraries for sale to streaming services. The existing players (and I like everyone am hoping for more competition in the space, but there aren’t any significant entrants on the horizon) have zero interest in dealing with anyone other than US majors – so even if you’re an established filmmaker or television producer looking to sell *one* (or a couple dozen) shows – you’re out of luck. The OTT networks want to deal in significant licenses, or own the shows outright (the Canadian producers of “Trailer Park Boys” had to sell their rights to the show before any new episodes were commissioned)

I’ve talked elsewhre in these comments threads I think that I, personally, (for almost two years now) have offered Netflix Canada a film *for free* that is currently already available on other countries Netflix’s. This means to make it available to Canadian audiences would likely only require maybe ten seconds on their end. In two years of phone messages and e-mails I’ve yet to even have anyone return a phone call… so working with Canadian content creators is demonstrably not a priority.

True, but seems like a lot of your arguments are somewhat short-sighted in the sense that you’re arguing how things are rather than how they could potentially play out.

“There’s also never going to be an obvious OTT interest in subsidizing the types of programming that many people enjoy like news, sports (which has no replay value and is a loss leader for most networks), educational programming and the like”

Youtube, Twitch and many others would like to disagree with you. While their usual fare of esports and whatnot don’t currently generate the same amount of revenue that the Superbowl does, there’s no reason this couldn’t change in the future.

“I understand that most people don’t like 99% of what’s on regular broadcast / cable (and I’m one of you) but at least that’s an ecosystem that can support diversity of programming because everything on there is *someone’s* favorite show.”

And there’s no reason that could or should change as we move to OTT.

“The existing players … have zero interest in dealing with anyone other than US majors”

Currently. Its unsurprising that as they’re trying to build their audience that they’re attempting to use the most popular shows to do that. Remember that Netflix and similar are still fighting large uphill battles against incumbent cable providers. Time Warner and Cox and whoever down in the states certainly haven’t been taking OTT laying down either. The whole “internet slow lane” crap that the FCC is currently considering comes directly from the US cable companies and is pretty much entirely an effort to reign in Netflix (or more precisely, to force Netflix to raise their rates closer to the historical gouging of the cable monopolies so that they don’t have to lower their own rates to compete.)

“I, personally, have offered Netflix Canada a film *for free* that is currently already available on other countries Netflix’s… I’ve yet to even have anyone return a phone call… so working with Canadian content creators is demonstrably not a priority.”

Or perhaps just working with you specifically is not a priority. The fact that you say the film is available on Netflix in other countries though suggests that there is something beyond simple technical reasons for them not to be interested. (Also, if its your film then how did you get it into other markets without them talking to you? And if its not your film, why are you offering it to them at all at any price?)

Basically though, everything that’s currently “wrong” with Netflix (and OTT in general) is _NOT_ inherent to the medium. Its a product of the current transition from powerful cable companies to powerful OTT companies. Oh, and I fully anticipate that 20 years from now, Netflix or Hulu or whoever will be the antagonists in whatever media battles arise at that time. Its easy to be the good guy when you’re new and catering to all your customers’ whims in order to increase your user base.. but its hard to maintain that once you’ve become the 800lb gorilla looking for the largest paycheck possible. And the cycle will continue as some new player looks to supplant the incumbents of the future.

Even with tax support, content is largely cheaper and easier to produce outside of Canada. Obviously more streaming services are going to emerge, but there is no evidence that any of the content they produce and sell to Canadian audiences will be made in Canada. Perhaps that is a good thing, since let’s be honest, Canadians are pretty terrible at making entertainment and our “culture” is identical in every way to the USA’s anyway. So at the end of the day, I believe the facts point to the Netflix model of production and delivery becoming ubiquitous. This will almost certainly help end of the heavily subsidized and mandated mainstream Canadian content industry. At the same time I also think few people will really care. Outfits like the CBC and CFB will continue on as much smaller niche specialty brands for people who think the “Logdriver’s Waltz” has cultural value or that Rick Mercer is funny.

Brad

The Cbc is a public broadcaster and they should be making far more then private nets in term,s of Canadian content.

Obviously the Globe would paint Netflix in a negative light. The Globe is 15% owned by Bell.

You would think these corporations don’t believe in capitalism. They want a capitalist market, but they want to be insulated from the core dictates of said marketplace. Time for the little boys to suck it up and deal with it. The public speaks with its dollars and we’re tired of the Canadian cable companies. Of course they’d rather expend more energy going after the little guy then improving their image or service. Soon these dinosaurs will be pushed out of the market, as they should be.

I have to say I am so sick and tired of hearing about threats, whether direct or implied, about the CRTC’s ability to flex its muscle against perceived threats against Canadian content. If the content quality is there, then people will watch it. If it isn’t why should people be forced to view lesser quality, simply because it is Canadian made. Makes no sense at all. Let there be an open market allowing the people decide what they like to watch. This will force people to pick up their game, producing more professional and desirous products, rather than relying on the CRTC to support their right to provide content, despite the fact they may not have the popular support of the viewing public.

I have that thought off and on as well. The problem of course is that if Canada produces something great, then it (or at least the people who made it) are quickly snatched up by the US at rates we can’t currently hope to compete with, even with subsidies.

I’m not sure what we could do in terms of a real solution to this problem. There’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem involved — we can’t really compete with the US industry until we’ve got some minimum level of quality (and thus money coming in to pay competitive wages,) but we can’t really get that minimum level established until we’re capable of competing with the US industry.

What might do it is if someone stepped up to the plate to intentionally lock down some superstar writers/producers/etc with the explicit goal of establishing a Canadian Hollywood.

Government funding probably couldn’t be used because they’d get slammed with fairness complaints but a private investment wouldn’t be hamstrung like that. Personally I think if Netflix wanted to run end-around on this whole CanCon issue, their best bet would be making one of their “Exclusive” shows a Canadian production. They’d still retain quality control so we’d get an amazing show with worldwide (and in particular, US) distribution potential and at the same time they could tell the CRTC “Look, we’re contributing to Canada and making something awesome so get off our backs!”

Of course whether that would be good in the long run is up for grabs — it could spell the end of CanCon laws if Bell and Rogers take up the same flag.. and of course once the laws are gone there would be nothing keeping these productions going but perhaps by that point, Canadian media would be of sufficient quality to be self-sustaining. Maybe.

Pingback: Geist on Netflix: Our champion goes channel surfing

It would likely be the end of BAD Canadian content. If TV and movie producers actually had to compete for airtime or exposure, perhaps the quality would improve.

Men bland alla Razzle glitter fanns svarta smoking pojkvän jackor. Från framsidan var de kvicka och chic, men att titta på klipp från bakom var att bli påmind precis vad en mästare här mannen är.Gallipoli fartyg att öppna för allmänheten

I’m sorry but even though I agree to let the online tv market open to new players in Canada, I think it’s a very skewed view to only look at Netflix services and the situation as it now. It might only be a little 4% of contribution to the canadian media fund in 2014 but at a larger scale, and looking at how this industry is growing fast, there are a lot of new platforms and services arriving in the market. It is more then important to establish a regulation on the streaming content in Canada. Public and private broadcaster are still the majors contributors to the canadian television industry, and although I think their business model has to be changed (I don’t even have cable TV at home), if they keep loosing their market shares on a year-to- year, their contribution will obviously cut down too. So both scenario are possible : Canadian content support and foundation will be wounded and tax payers will have to pay more the broadcasters’ bundles for content that is not as diversified. Long term, we’ll face a basic economic concept : adverse selection. I think there are ways to face the major changes of the industry but it sure isn’t by letting abroad content flooded our online tv services.

Mel

Regarding these ‘so called tax credits’; is it not the intent of provincial and/or federal governments, by offering these credits, to attract and/or maintain a film and tv series industry in their particular region? Is it therefore but a means of attracting an industry and not a real cost for the public purse? As I understand it, no public funds are spent, rather, if the tax exemption offer is not accepted no spin-off economic activity is generated. If the offer is accepted the region benefits through employment and purchased local services consumed. My argument is: the ‘tax credit’ is but an abstraction and isn’t truly a value to be included in the CMF financing list. It is but potential revenue never realized, for the greater purpose of generating economic activity; very much in line with varying Royalty Rates on natural resources.