The federal government placed a big bet in this year’s budget on Canada becoming a world leader in artificial intelligence (AI), investing millions of dollars on a national strategy to support research and commercialization. The hope is that by attracting high-profile talent and significant corporate support, the government can turn a strong AI research record into an economic powerhouse.

Funding and personnel have been the top policy priorities, yet other barriers to success remain. For example, Canada’s restrictive copyright rules may hamper the ability of companies and researchers to test and ultimately bring new AI services to market.

What does copyright have to do with AI?

My Globe and Mail column notes that making machines smart – whether engaging in automated translation, big data analytics, or new search capabilities – is dependent upon the data being fed into the system. Machines learn by scanning, reading, listening or viewing human created works. The better the inputs, the better the output and the reduced likelihood that results may be biased or inaccurate.

Copyright law crops up because restrictive rules may limit the data sets that can used for machine learning purposes, resulting in fewer pictures to scan, videos to watch or text to analyze. Given the absence of a clear rule to permit machine learning in Canadian copyright law (often called a text and data mining exception), our legal framework trails behind other countries that have reduced risks associated with using data sets in AI activities.

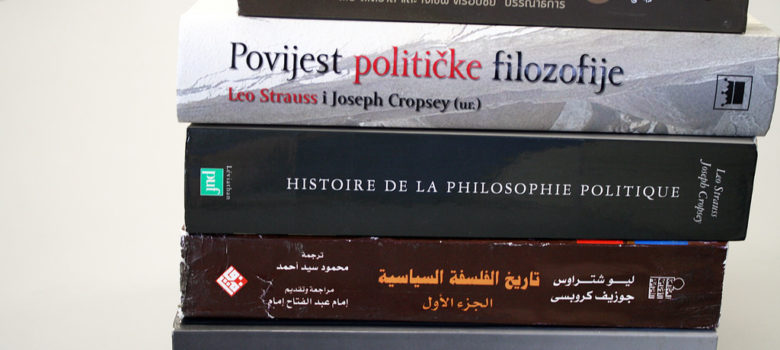

For example, consider how machines are taught to translate languages. Last year, the United Nations released 800,000 manually translated documents in the six official UN languages (English, French, Spanish, Arabic, Russian, and Chinese) for machine use. By releasing documents containing perfect translations in multiple languages, the data set helps create better automated translation systems. Indeed, official government documents have been an important data source for automated translation since they offer professionally translated materials of identical content.

Yet the downside of relying on these documents is that treaties and diplomatic correspondence rarely mimic everyday speech. Better systems would benefit from a broader range of materials such as translated popular books or television shows. The goal is not to republish or compete with copyright materials, but rather to ensure that researchers and AI companies can mine the text and data for informational analysis purposes.

Canadian courts have ruled that fair dealing – the copyright law’s foundational exception that permits use of materials without the need for prior permission – is a user’s right that should be interpreted in a broad and liberal manner. There are several purposes that would permit some text and data mining activities, notably exceptions for research, education, and private study. However, given Canada’s emphasis on the commercial benefits of AI, the law may not offer sufficient flexibility to safely move from the lab or classroom to the market.

There are two ways to overcome the copyright AI barrier. First, Canada could emulate the U.S. fair use model by making the current list of fair dealing purposes illustrative rather than exhaustive. The U.S. exception is open to any purpose, as striking a fair balance depends upon the use of the work, not the purpose of the copying. Since machine learning does not harm the primary purposes of the original work, most text and data mining will qualify as fair use.

Second, other countries have tried to address the issue by creating a specific exception for text and data mining or computer informational analysis. For example, Britain’s exception allows copies of works to be made without permission of the copyright owner for the purposes of automated analytical techniques to analyze text and data for patterns, trends, and other information. The law does not allow contracts to restrict data mining activities, but the exception is limited to non-commercial research.

Text and data mining exceptions are becoming increasingly popular – Japanese law features an exception and the European Union has been debating adding one as well –

meaning Canada risks falling behind in race to the commercialize AI research because of an overly restrictive copyright law. With Innovation, Science and Economic Development Minister Navdeep Bains and Canadian Heritage Minister Mélanie Joly set to lead a review of copyright law later this year, clearing away unnecessarily restrictive legal barriers must be on the agenda.

Pingback: Why Copyright Law Poses a Barrier to Canada’s Artificial Intelligence Ambitions – infojustice

not if there’s money in it.

the open city data is an example. You make an app that makes money from their data and they’ll want in.

taxis, sjnowplows, buses… (NOW for the fun part. shopping centers with high incident breakin-ins in their parking lots)

scrapping to make imitations? on the list.

lawsuits to prevent home-info like, say, sewage-line life-times?

next.

packrat