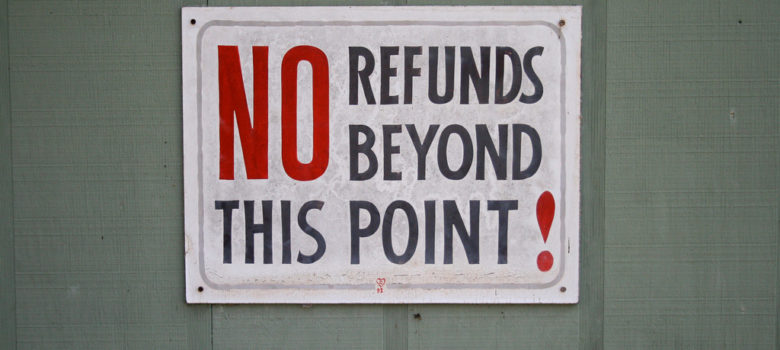

With the Canadian copyright review likely to commence in a few weeks, the hysteria associated with fair dealing – much of it disconnected from the economic reality of spending on copyright works since 2012 – promises to hit a fever pitch. Access Copyright and the Writers Union of Canada got off to an early start in their reaction to a lawsuit filed last week by Canadian school boards and Ministries of Education seeking a refund for years of over-payments that has cost schools more than $25 million. The groups described the lawsuit as “an outrageous attack on Canada’s writers” and “simply intimidation.”

As with much of the debate around fair dealing in Canada, the reality is far different from the rhetoric. I’ll be posting all week on fair dealing – it is fair dealing week in Canada – starting with a summary of this lawsuit. Canadian schools paid millions of dollars to Access Copyright from 2010 to 2012 for copying in advance of the actual tariff being set by the Copyright Board of Canada. From 2013, they ceased payments on the grounds that they no longer needed to rely on the Access Copyright licence. It took several years for the Copyright Board to retroactively set the applicable tariff. Access Copyright initially sought $15 per student, the schools later paid $4.81 per student, the Copyright Board ultimately set the tariff at $2.46 per student. As I blogged when the Copyright Board decision was released:

a close look at the Copyright Board’s analysis reveals that it found that 97.2% of copying from books, 98.1% of newspapers, and 98.5% from periodicals qualified as fair under a fair dealing analysis. In other words, virtually all copying of books, newspapers, and periodicals in the large sample reviewed by the Board is covered by fair dealing and does not require a licence from Access Copyright. Moreover, the Board found that copying 1 to 2 pages from a book is insubstantial and does not even require a fair dealing analysis.

Moreover, while not directly discussed in the case, it is worth noting that the fair dealing analysis focused almost entirely on the decisions from the Supreme Court of Canada. This will not come as a surprise to copyright lawyers, but it runs counter to Access Copyright and its supporters attempts to paint the current Canadian approach as a direct result of the 2012 legislative reforms.

Access Copyright called the Copyright Board decision “deeply problematic” and took its case to the Federal Court of Appeal. A unanimous court rejected the appeal in February 2017:

It may well be that the Board’s methodology is not perfect, but again, given the particular circumstances of this case, I have not been persuaded that its overall determination that a large portion of the exposures were fair (again this was much less than the numbers proposed by the Consortium using a similar statistical approach) was unreasonable because of the method it chose to weigh the evidence in forming its overall impression of the fair dealing factors.

In fact, the Federal Court of Appeal emphasized the reasonableness of concluding that the aggregate amount of copying was not unfair – less than 10 pages per student per month – noting:

In explaining why looking at the aggregate volume of copies was not helpful to its assessment of whether the copies were widely distributed, the Board reasonably applied the Supreme Court’s teachings in CCH and Alberta. I find no reviewable error on the part of the Board in this respect. In fact, this finding is reasonable even if one were to consider that the overall number of copies represents approximately 90 pages per student per year. I agree with the Consortium that this figure does not support the view that this factor could only tend to a conclusion that the dealing was not fair.

The Federal Court of Appeal did send back one aspect of the Copyright Board ruling to the board to reconsider. It issued its decision in January 2018 with no further changes to the tariff.

Having overpaid by millions of dollars (based on Copyright Board analysis that was upheld by Federal Court of Appeal), the education groups asked for a refund of the overpayment. When Access Copyright refused – it said it was holding the money to cover later copying under a licence for which schools had opted-out – the schools filed a lawsuit for a return of the overpayment.

That’s it. That’s the “attack” on writers, whose collective was paid more than the copying was worth as determined by the Copyright Board. In fact, the collective put the money aside knowing that there were legal questions about it and it now refuses to issue a refund. That leaves educational institutions without tens of millions of dollars which they paid in good faith. The court will be asked to consider both the overpayment and the question of opting-out of the tariff for later years (Howard Knopf and Ariel Katz have written extensively about the issue), but the claim that this is an attack on writers is a remarkable distortion of the facts.

Pingback: Fair Use/Fair Dealing Week 2018: Day 1 Roundup | ARL Policy Notes

Pingback: Fair Use/Fair Dealing Week 2018: Day 1 Roundup | Fair Use/Fair Dealing Week

Pingback: Fair Dealing and the Right to Read: The Case of Blacklock's Reporter v. Canada (Attorney General) - Michael Geist

Pingback: This Week’s [in]Security – Issue 49 - Control Gap | Control Gap