My post this week on the recent CRTC’s television licensing decision elicited a strongly worded response yesterday from the Writers Guild of Canada. My original post made two key points. First, responding to Kate Taylor’s assertion that CRTC Chair Jean-Pierre Blais has offered no consistent strategy to the challenges facing the Canadian television production industry, I noted that over the course of the past five years, Blais has charted a very clear path toward making Canadian policy and regulation relevant in the digital age by promoting a competitive marketplace for Canadian creators, consumers, broadcasters, and broadcast distributors.

Second, I defended the recent CRTC decision on several grounds, including the need to address the gap between regulated and unregulated services (such as Netflix), the already-significant public support for Canadian content creation, the incentives for Canadian broadcasters to invest in original content, and the fact that Canadian broadcasters contribute a very small slice of the overall financing of domestic fictional programming which suggests that the harm to the sector from a further reduction is overstated.

The WGC response takes issue with the emphasis on competition, alternately claiming that Canadian television has always competed in the marketplace but that it cannot compete without regulatory mandates requiring Canadian broadcasters to invest in original Canadian programming. While some of the response is confusing or inaccurate (it mistakes the $2.6 billion Canadian television production market for the Netflix Canadian market, refers to a 1999 Blais television policy when Françoise Bertrand was CRTC chair at the time, discounts co-productions that often feature Canadian themes or iconic stories and generate significant Canadian employment and foreign investment), at its heart is the WGC view that longstanding regulations and market protections should continue or be expanded in the digital environment. In today’s world, Canadians enjoy far more choice, broadcasters face far more competition, and creators can tap into a myriad of new markets and potential investors, but the WGC vision is that old-style regulations should remain in place.

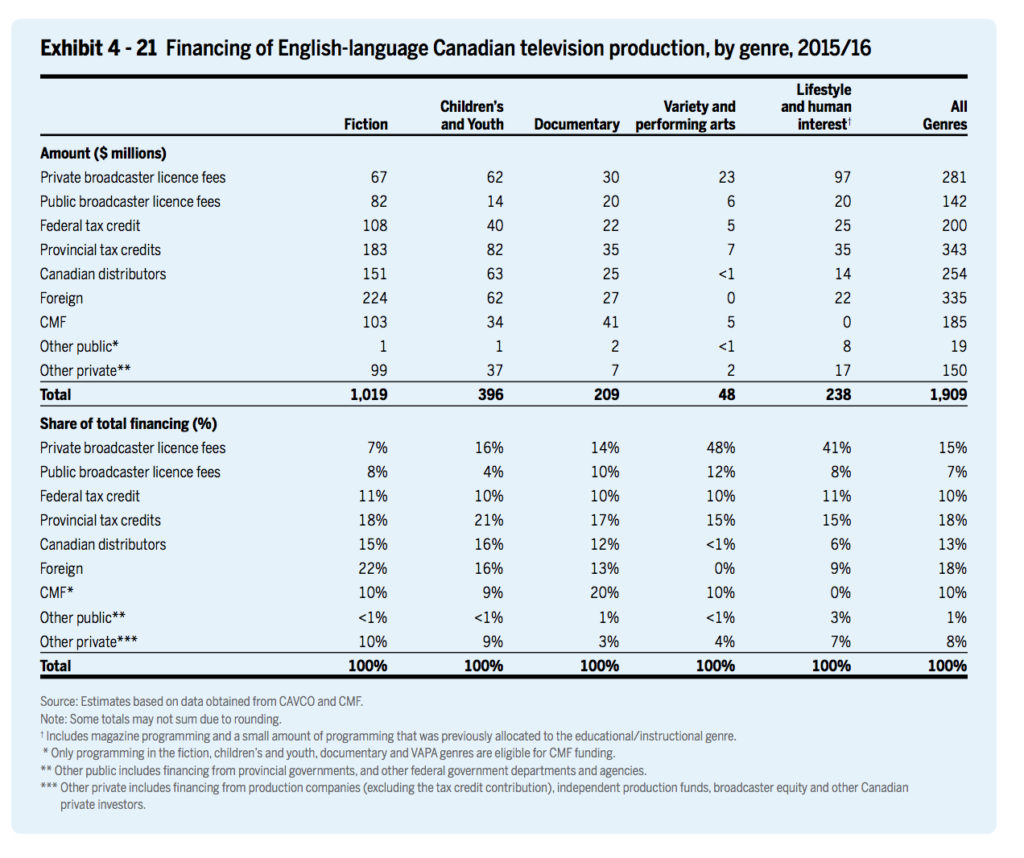

Perhaps nowhere is that more apparent than in the WGC’s final paragraph, which claims that a $40 million drop in broadcaster spending amounts to a 25% decline that it previously described as devastating. The claim simply ignores the reality of how Canadian television is financed today. As I note in my post, private broadcasters today are minor players, contributing only 9% of total financing for Canadian fictional programming. To again quote the CMPA:

With fiction productions, the largest share of financing came from provincial and federal tax credits; the fiction genre also attracted the most foreign financing among all genres. Children’s and youth productions also derived the largest share of their financing from tax credits, followed by broadcaster licence fees. Distributors also accounted for an important part of the financing picture for the fiction, and children’s and youth genres. In the VAPA and lifestyle and human interest genres, most financing came from broadcaster licence fees.

The WGC argues that English and French language production should be treated separately, yet the CMPA data for English-language only production does little to change the analysis. In fact, broadcaster contributions for fictional programs in English are even lower as a percentage of total financing (7% in English vs. 9% overall) and rank as the smallest source of financing among tax credits, foreign funding, and the Canadian Media Fund. In fact, foreign funding is more than three times as large as private broadcaster funding for fictional English-language programs. An overall drop of $40 million for fiction, children’s programming, and documentaries would still just result in a decline of 2.5% of overall financing or 1/10th of what the WGC claims. Further, while it argues that the broadcaster window is needed to trigger other support, that too is changing with new CAVCO rules that allow online platforms to meet the “shown in Canada” requirement.

CMPA Profile 2016, Page 56, http://www.cmpa.ca/sites/default/files/documents/industry-information/profile/Profile%202016%20EN.pdf

The issue ultimately comes down to two different perspectives of Canadian content in the digital environment. The CRTC view – one that I defended in my post – is that Canadian creators can compete on the global stage, creating compelling content that finds investors and interested broadcasters from around the world. There is still a need for public support in this digital environment (a billion dollars is hardly insignificant) but the CRTC has confidence in Canadian creators and a belief that relying on outdated policies that regulate how content is broadcast or financed make little sense in a globally competitive marketplace that now involves video competition from giants such as Netflix, Google, and Facebook.

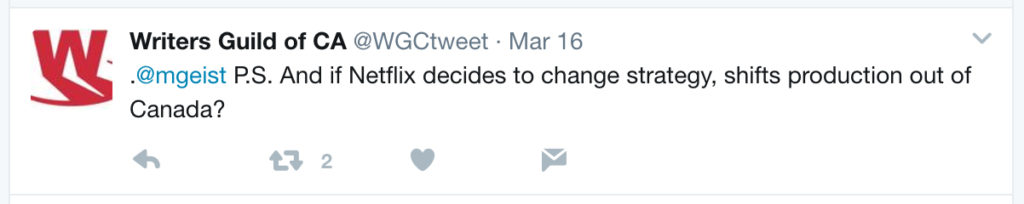

The WGC perspective has seemingly little confidence in the ability to compete without regulation (the open letter says as much). The WGC response and its policy positions in recent months have been all about how Canada can’t compete – can’t compete without mandated Netflix payments, can’t compete without ISP payments, can’t compete without mandated broadcaster investments, and can’t compete without simultaneous substitution. In fact, when I wrote earlier this year about how foreign financing has now surpassed virtually all other sources of funding for English-language television production, the WGC response was to express fear that Netflix might change strategies and stop funding Canadian content:

@WGCtweet, March 16, 2017, https://twitter.com/WGCtweet/status/842406618931294208

Yet Netflix spends millions on production in Canada not because it faces a regulatory requirement, but rather because the entire package – innovative creators, tax credits, good partners – offers a compelling reason for doing so. Indeed, the data shows that the Canadian industry has thrived in recent years for reasons that have little to do with pre-digital regulations with a huge shift in Canadian television production financing from domestic funding to foreign investment.

As Minister Joly crafts her digital Cancon policy, she is faced with the choice of competing perspectives: a policy based on confidence that Canadian creators can compete on the world stage based on a policy framework that attracts investment and provides support for creation and promotion or one premised on the fear that success is only possible when the government mandates contributions from broadcasters and Internet companies.

I read the WGC piece. Not surprisingly, it completely confirmed my previous observation about their bizarre sense of entitlement to a competition-free environment.

Also not a surprise was the absence of a comments section. They’re okay naming and firing shots at someone, so long as they fell they’ve had the “final word”. You’d think such a pointed piece would beg for feedback from their other members, as well as those they’re trying to smear. To me, that’s somewhat cowardly.

Exactly, the truth hurts and they don’t want to hear it, period.

Your analysis does not take into account that a Canadian broadcaster licence fee is required to trigger the CMF and the tax credits for Canadian content television productions. Without that trigger the rest of the financing is moot. Canadian broadcasters licence fees have been falling and producers have by necessity needed to find other sources, which would also explain the increase in foreign funding. Ask DOC about how hard it is to produce documentaries

In Canada because broadcasters are not licensing them much anymore. DOC producers are finding it very difficult if not impossible to finance their projects without a Canadian broadcaster involved. If Canadian broadcasters decrease their spending on licensing Canadian content there will most likely be a ripple effect in the decrease of overall Canadian production levels, based on past experience. This is indeed what happened to Canadian drama after the CRTC’s 1999 tv policy went into effect.

The problem with Michael Geist’s vision of the Canadian broadcasting future is that it leaves little place for high quality indigenous Canadian production. Lower Canadian content requirements in terms of hours broadcast and spending will only encourage reliance on more U.S. programming. The damage began with the results of the Let’s Talk TV proceeding and has been confirmed by the May 15 licence renewals of the television services owned by the large broadcasting ownership groups. Contrary to what Michael Geist asserts, net neutrality is a telecommunications issue concerning differential pricing by Internet service providers (ISPs) that has no direct implications for Canadian creators of high quality television programs.

The production of high quality indigenous Canadian television programs in the under-represented categories (drama, POV documentaries, children’s programs) has been relatively successful over the last two decades, largely due to case-by-case CRTC requirements and government financing from tax credits and institutions such as the Canada Media Fund. A television broadcaster’s commitment to air such programs is necessary to obtain Canada Media Fund, and federal and provincial tax credits, among other funding sources.

The legacy of Jean-Pierre Blais will be to have precipitated the decline of under-represented programs (aka programs of national interest). Blais has implemented a populist agenda focused on lower prices for consumers as if television broadcasting should be guided by the economic objectives and purpose of the Telecommunications Act and the Competition Act, rather than the cultural objectives of the Broadcasting Act. In accordance with this agenda, lower prices for consumers are provided in the form of less Canadian content (which is more expensive to produce than acquiring U.S. programs) and more laisser-faire. Despite the rhetoric, there is nothing innovative about this libertarian itinerary.

Jumping on the digital band wagon, as Micheal Geist advocates, means killing off high quality indigenous Canadian production – without a replacement. Digital media generate relatively little high quality original content (in terms of total hours broadcast), and very almost no high quality identifiably Canadian content. Netflix, for example, broadcasts a small number of high quality American original prime-time tv shows backed by a library of U.S. movie and television series reruns. Once we get past the Silicon Valley agitprop, Netflix is no more than an unlicensed television channel offering subscription video-on-demand (S-VOD). It does not produce identifiably Canadian content in any significant volume. Why should Netflix and other such U.S. programming services get a free ride in Canada?

Without the equitable treatment of Canadian and non-Canadian television programming services, the protection and enhancement of Canada’s distinct identity will be diminished. The solution is to gradually bring digital programming services into the Canadian television broadcasting environment. This could begin with governments applying federal and provincial sales taxes to programming services. The CRTC could treat Internet programming services as VOD programming undertakings – exempting such services subject to their meeting certain requirements. The Commission has already created a category of hybrid VOD services which could serve as a model for this kind of approach.

Canadian broadcasters on the basic service, such as CBC, CTV, Global, Radio-Canada and TVA, generally invest in high quality original Canadian programs. Not only is their production financing crucial, but so is their emotional commitment, promotion and scheduling. However, unlike these basic services, the discretionary and on-demand services do not have strong incentives to create original programming in the under-represented categories, unless the CRTC directs them with precise conditions of licence. These services will only invest in high quality original Canadian programming if required to do so. Thus, for example, three days after the CRTC announced the licence renewal of Séries+ for the next five years, relieving the French-language specialty service of its obligation to spend $1.5 million a year on original Canadian drama, its owner, Corus Entertainment of Toronto, cancelled all three of Séries+’s projects in development. http://www.journaldemontreal.com/2017/05/18/series-bientot-sans-contenu-quebecois No requirement, no more spending.

With his approach to the licence renewal of the television services owned by the large broadcasting ownership groups Jean-Pierre Blais has contributed to the dismantling of the current television broadcasting system and its replacement with fewer original Canadian programs in the high cost under-represented categories, such as drama. This will lead to reduced opportunities to view Canadians on television and a consequent loss in our national sovereignty and identity.

Nonsense, the welfare check must be removed to motivate.

In part your right the harm was done at the lets talk debate but more with groups unwilling to change just look at some of the ideas.

80% Cancon on all channels

70% tax on Netflix and other streaming services

Ban all non Canadian channels

In short become like North Korea.

Perfect your trading strategy on a totally free Demo account 1000$;

Most Innovative Binary Option Broker!

Trading simplified!

Interactive education system!

No credit card, no phone number required.

Mobile apps for Android and IOS;

Minimum deposit just 10$;

Innovative Trading.

Open an account and start trading right now!

http://options-account.deadline.mobi

Michael Geist accurately describes the Writers Guild of Canada’s open letter re: his blog post about the recent CRTC television licensing decision as strongly worded. It’s strongly worded because poor, incomplete analysis is extremely frustrating.

In Geist’s response, “Can CanCon Compete?”, he continues to either misunderstand or misrepresent the scale and impact that a $40 million annual decrease in broadcaster spending on programs of national interest (PNI) would have.

There is an irony in Geist claiming that the WGC “ignores the reality of how Canadian television is financed today” when screenwriters live and breathe that reality every day. And let’s set aside that national broadcasters contributing single-digit percentages to financing national content production is actually a bad thing, and shouldn’t be shrugged away as being normal or acceptable. Looking at the real impact of the CRTC’s decision, Geist’s analysis still overlooks or minimizes the potential multiplier effect of reduced broadcaster spending. While CAVCO has recently changed its rules to allow online platforms to meet the “shown in Canada” requirement, the CMF still requires a broadcaster trigger — i.e. “Eligible Licence Fees” — that must meet a minimum, threshold amount. But this goes beyond eligibility requirements — tax credits generally operate on a percentage of qualified labour, and the CMF generally caps its contribution as a percentage of budget. If labour and/or expenditures go down, then public funding goes down. They are tied together. Further, certain stories require certain budget levels to be effectively told, and foreign financiers don’t automatically increase their financing simply because Canadian broadcasters have stepped away. Less broadcaster investment may result in lower budgets, or in productions scrapped entirely because they can’t close the financing gap. This is not just about one number in a data table viewed in isolation.

Moreover, talent doesn’t want to work in a declining — or, frankly, even in a potentially declining —sector. Canada already loses talent yearly to Hollywood, where the talk isn’t about how financing will “only go down 2.5%” in English PNI (again, it will likely be more), but about growth in budgets that were already much larger than those supported by a small Canadian market. To put it in perspective, in Alberta’s current recession, called one of the most severe in its history, the province’s GDP “only” contracted by 3.8% in 2016. Talent drain is a problem we’re trying to reverse, not accelerate.

But on one point, Geist and the WGC appear to be in general agreement: At the centre of this debate is whether or not a robust cultural policy framework, which includes meaningful public funding and regulation, can be replaced, in whole or in part, by “confidence.” Geist claims that the WGC, “has seemingly little confidence in the ability to compete without regulation.”

Such statements come from the Little Engine That Could school of cultural economics, and confuse a belief in the talent and quality of our creators with the structural and economic challenges they are faced with. (We know, and the world knows, about Canadian screenwriter talent — just look at the domestic and international success of shows like Cardinal, Murdoch Mysteries, Private Eyes, Orphan Black etc. etc.) But if having a cultural policy, with significant levels of public funding, or regulatory requirements of private entities, or both, displays a lack of confidence, then the following countries also have “little confidence in their ability to compete”: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Norway, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

In the WGC’s initial open letter, http://www.wgc.ca/news/index.html?news_id=726&return_to_index=true we highlighted three countries that already do more financially for their national content — in absolute dollars, on a per-capita basis, or both — than English Canada. Yet Michael Geist cheerleads us towards doing less, implies that we should embrace declines in broadcaster spending with good spirits (while also arguing that it’s in broadcasters’ interest to spend), and counsels bootstraps and “confidence.” Yes, he’s still wrong.

Michael Geist appears to misunderstand the economics of broadcasting and Canadian content. Promoting a competitive marketplace may be appropriate for consumers and broadcasting distribution undertakings (carriers). It is not appropriate for Canadian broadcasting programming undertakings and creators, at least not in the way conceived by Jean-Pierre Blais’ CRTC.

Broadcasting and high quality television program production are characterized by huge economies of scale. Relatively small atomized units can not realize the cost, distributional and promotional savings of giant multinational corporations. It is difficult for Canadian companies to compete with the U.S. motion picture studios, the U.S. television networks, HBO, Netflix, YouTube, etc. without regulatory protection. Digital technology changes none of this.

So why should Canada try to compete with the U.S. juggernaut? Why not abandon broadcasting regulation and leave broadcasting (including digital media programming undertakings) to more economically efficient firms, as we have done with automobiles? There is an automobile industry located in Canada. According to Wikipedia, Canada is the ninth largest automobile producer in the world. But, this production consists of assembly plants controlled by U.S. and Japanese carmakers.

There are certain activities that Canadians do not want to submit to the unfettered competitive marketplace. Military defense is one example. No one suggests that Canada’s national defense should be subcontracted to U.S. multinational firms, although this might be a more economically efficient outcome. The same kind of argument applies to broadcasting. Section 3 of the Broadcasting Act declares that the Canadian broadcasting system shall be effectively owned and controlled by Canadians and that it is a public service essential to the maintenance and enhancement of national identity and cultural sovereignty. In other words, broadcasting is one of the industries that contribute to the cultural defense of the nation.

Canadian cultural policy, including broadcasting policy, is intended to safeguard, enrich, and strengthen Canadian identity and cultural diversity, and maintain a standard of quality comparable to that of the United States and the other industrialized countries. In the United States, the cultural industries are generally considered no different from any other industry, and specific policy support measures are believed unnecessary. In Canada and other industrialized countries, government subsidies and regulatory measures ensure that domestic cultural products are available in the home country. The United States would like to see an end to all “discriminatory” policies against their exports, including cultural products. However, from the Canadian point of view, Canada’s market for cultural goods and services is one of the most open in the world and pressures for greater openness must be balanced against the desire to retain some space (“shelf space”) available for Canadian cultural products and services that Canadians may choose if they so wish.

This is particularly important for English Canada which shares a long border with the United States, a comparable history, similar kinds of institutions, and a common language. What happens in the United States media is not filtered by the language barrier as it is in Québec – and in nearly all other small to medium-sized countries whose domestic firms do not enjoy huge scale economies.

The idea of Canadian companies competing on the “world scene”, “creating compelling content that finds investors and interested broadcasters from around the world” in the face of the U.S. studio and network giants is pie in the sky. This kind of export-oriented strategy is an outdated relic from the 1990’s (Jean-Pierre Blais first worked at the CRTC during these years) when companies like CINAR, Telescene and Nelvana produced drama programs using various devices to reduce or camouflage their Canadian creative elements in order to peddle them to foreign markets, especially the U.S. market. Canadian television production companies continue to work at partnering with and selling to foreign entities, but they have learned that success is difficult and, if it can be achieved, will come from identifiably Canadian stories and creative elements.

A new “flexible and supportive” regulatory regime was installed by the CRTC in the course of the 2011 Francophone television licence renewals. The new regime produced a decline in spending on programs of national interest (PNI), especially drama and long-form documentaries, by Francophone general interest television in 2012-13. This result confirms the notion that the solution to the problems encountered by original Canadian programming in the under-represented categories resides in clear and precise conditions of licence, licensee by licensee.

Michael Geist has provided no evidence that the regulatory policies dismantled by the Let’s Talk TV proceeding were ineffective, or that the CRTC’s recent licence renewal decisions will improve the situation. They will make the situation worse and Corus’ decision to cancel three drama projects in development is an indication of this. (http://www.journaldemontreal.com/2017/05/18/series-bientot-sans-contenu-quebecois) Because there are no longer any requirements for original programming in the under-represented categories, such programming will diminish in the coming years. Canadian television program production in the under-represented categories needs more support, not less.

You want to create jobs then count all shows filmed in Canada as Cancon.