Canadian Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault rose in the House of Commons yesterday for the second reading of Bill C-10, his Internet regulation bill that reforms the Broadcasting Act. Guilbeault told the House that the bill would level the playing field, that it would establish a high revenue threshold before applying to Internet streamers, would not impact consumer choice, or raise consumer costs. He argued that even if you don’t believe in cultural sovereignty, you should still support his bill for the economic benefits it will bring, warning that Canadian producers will miss out on a billion dollars by 2023 if the legislation isn’t enacted. He painted a picture of Internet companies (invariably called “web giants”) that have millions of Canadian subscribers but do not contribute to the Canadian economy,

Guilbeault is wrong. He is wrong in his description of the bill (it does not contain thresholds), wrong about its impact on consumers (it is virtually certain to both decrease choice and increase costs), wrong about the contributions of Internet streamers (who have been described as the biggest contributor to Canadian production), wrong about level playing field claims (incumbent broadcasters enjoy a host of regulatory benefits not enjoyed by streamers), wrong about the economic impact of the bill (it is likely to decrease investment in the short term), and wrong about cultural sovereignty (it surrenders cultural sovereignty rather than protect it).

With the bill starting its Parliamentary review, this is the first in a new series of posts on why a careful examination of the data and the bill itself reveals multiple blunders. There are good arguments for addressing the sector, including tax reform, privacy upgrades, and competition law enforcement. There are also benefits to updating the Broadcasting Act, but in an effort to cater to a handful of vocal lobby groups over the interests of the broader Canadian public, Guilbeault’s bill will cause more harm than good. The series will run each weekday for the next month, first addressing the weak policy foundation that underlies Bill C-10, then a series a posts on the uncertainty the bill creates, a review of the trade threats it invites, and an assessment of its likely impact on consumers and the broader public.

The series begins with a post on the fictional Canadian content “crisis.” Canadians can be forgiven for thinking that the shift to digital and Internet streaming services has created a crisis on creating Canadian content. Canadian cultural lobby groups regularly claim that there is one (Artisti, CDCE) and Guilbeault tells the House of Commons that billions of dollars for the sector is at risk. Yet the reality is that spending on film and television production in Canada is at record highs. This includes both certified Canadian content and so-called foreign location and service production in which the production takes place in Canada (thereby facilitating significant economic benefits) but does not meet the narrow criteria to qualify as “Canadian.” I have written before about the need to revisit the Canadian content qualification rules which enable productions with little connection to Canada to receive certification and some that directly meet the goal of “telling Canadian stories” that fail to do so.

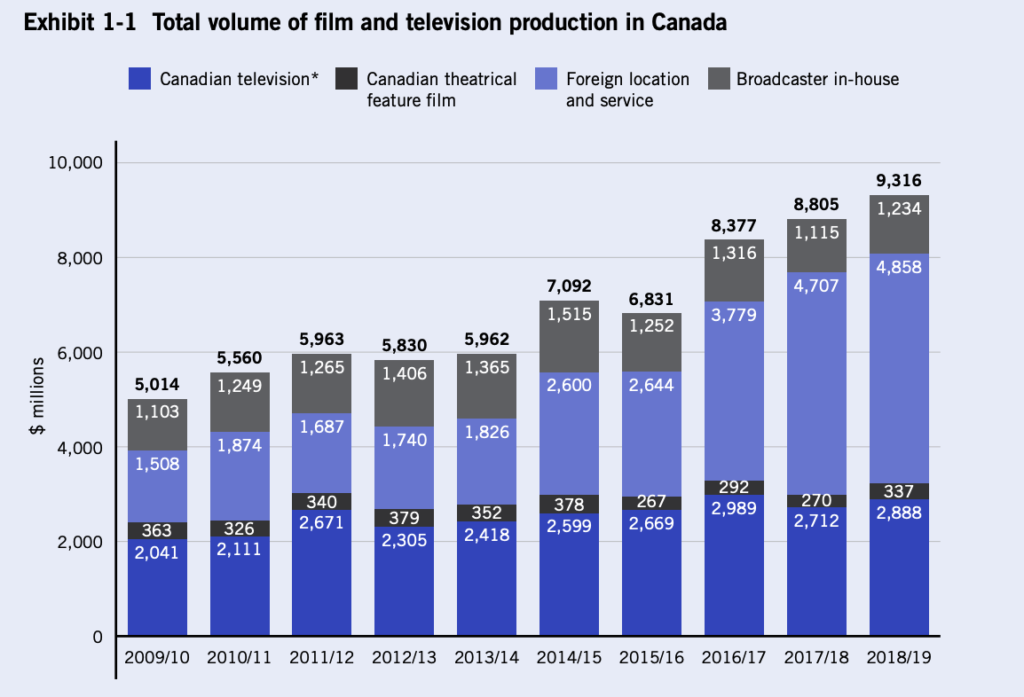

The data on this issue is unequivocal. The overall financing picture shows an industry that has had record amounts of investment in film and television production with the total amount nearly doubling over the past decade. Further, certified Cancon has also grown in recent years, with the top two years for certified Cancon television production occurring over the past three years. In fact, last year was the biggest year for the production of French language Cancon over the past decade.

CMPA Profile 2019, Exhibit 1-1, Pg. 7, https://cmpa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CMPA_2019_E_FINAL.pdf

The data at the provincial level provides further confirmation of record-setting production. Earlier this year, Ontario Creates, the Government of Ontario’s agency for cultural creation, touted a “record breaking year” for Ontario’s film and television production sector, citing more than $2 billion in production spending for 343 productions. Of the $2.1 billion, there was a near-even split between domestic and foreign production: $1.1 billion in foreign production and $1 billion on domestic productions.

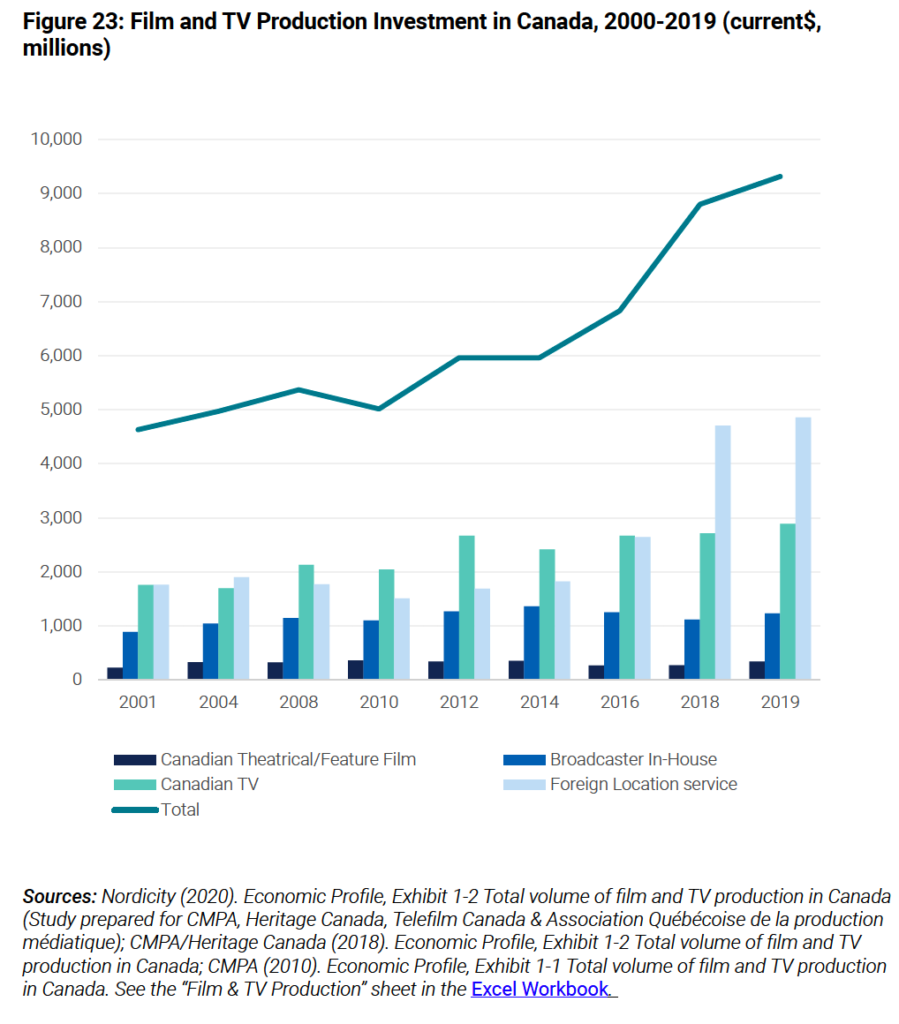

In fact, this week Carleton professor Dwayne Winseck released his annual review of the state of the network economy in Canada. Drawing from multiple sources, he too finds that film and television production investment in Canada has continuously increased for two decades, most recently “driven by massive investments from streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime.”

Figure 23, Winseck, Dwayne, 2020, “Growth and Upheaval in the Network Media Economy, 1984-2019”, https://doi.org/10.22215/cmcrp/2020.1, Canadian Media Concentration Research Project, Carleton University.

Notwithstanding the rhetoric, the reality is the politicians and regulators know this to be the case. For example, CRTC chair Ian Scott last year said that Netflix is “probably the biggest single contributor to the [Canadian] production sector today.” Further, at the press conference introducing the bill, Guilbeault acknowledged that the Internet companies are already investing in Canada, but argued that the bill was needed to ensure those investments were not voluntary. Yet production in Canada has grown for years not because of mandatory regulations, but because it is competitive on the world stage. As future posts in this series will demonstrate, Bill C-10 jeopardizes that position.

A few thoughts:

Guilbeault has brought the worst of Quebec’s cultural politics to the federal scene. Draconian policies are justified by claiming the targets of the legislation are a never ending cultural threat.

Guilbeault seems to be following Catherine McKenna’s playbook. She said that repeating something loud enough and often enough is a good strategy to get others to believe it.

SNC Lavalin demonstrated that this government can be bought, so what is the quid pro quo for this legislation?

I’m not sure why it seems to be a prerequisite for succeeding in politics to be stupid or avaricious or both.

It seems as if most of them start very soon forgetting who they are supposed to be working for and start working instead for those who are going to give them cushy, highly paid jobs when they quit politics.

Pingback: ● NEWS ● #MichaelGeist #CRTC #canada ☞ The Broadcasting Act Blunder… | Dr. Roy Schestowitz (罗伊)

YOU should be the Minister, NOT Mr. Guilbeault. It’s high time we had intelligence and wisdom in power instead of blood sucking corporate cronies or power hungry control freaks.

You continue to make the same mistake over and over again. You continue to conflate the numbers for service production and for Canadian content into one category. It is very true, as Dwayne Winseck points out, that production in Canada is up and it is because of money being spent by the big streamers – Netflix, Amazon Prime and would add Apple. However these expenditures are not connected in any way to the Canadian Broadcasting system nor to the changes coming from Bill-C10. They are driven first and foremost by an increase in global production expenditure due to the entry of Amazon and Apple – and others – into the global markets. Secondly, due to the fact that Canada is an excellent manufacturing sector for production.

The problem that Bill-C10 starts to solve is not a production problem but a distribution problem. The arrival of the big streamers is going to disrupt the current distribution model for Canadian broadcasters. Traditionally US content was sold through the Canadian broadcasters but not it coming directly to the Canadian consumer. This disruption is both a threat and an opportunity for Canada. I, for one, am of the view that it is a great opportunity as global markets are quickly creating more opportunity for content producers. Canada should be in a strong position to compete. However countries around the world are recognizing that the streaming platforms need to be brought under their regulations to assure their own services are carried on them and that their regulatory objectives are not lost with the entry of foreign players. Bill-C-10 is a start – and needs some work – but it takes us in the right direction.

There is no distribution problem.

There was a distribution problem fifty years ago, when the Canadian content rules came in, as the only Canadian distributors were CTV and CBC.

Now the internet allows for unlimited distribution. Content producers can sell to Canadian broadcasters, foreign broadcasters, or streaming platforms. If no one wants to buy the product they can upload it to Youtube or set up their own website.

We don’t require booksellers to carry a certain amount of Canadian content, so why should we do so for broadcasters and streaming platforms ?

You are making my point but talking about it differently. The traditional Canadian system was based on a captive market. The foreign content came in through the system and part of those revenues went towards the production of Canadian content.

The streaming platforms are eroding that distribution system and replacing it with a direct to consumer model. However that model will be dominated by platforms including aggregators like Amazon and Apple. To be clear, I am not saying this is a bad thing. What Bill-C10 is trying to do is replace the revenues that came from the closed system with those of open system. The concept being that the contribution is the same and is in exchange for open market access.

What I meant by distribution problem is that the traditional system is shrinking. This means that money going into the system is shrinking as is the distribution footprint on the system. Both impact Canadian production. Therefore the broadcasters need to move internet distribution models both inside and outside Canada to replace what they are losing as the current system shrinks.

Here are the problems with your arguments:

Open markets do not require companies to pay fees to access them. Paying fees means it is a controlled market.

Companies do not have a right to exist. When new companies come along that provide a better product at a lower price, the old companies and their suppliers need to adapt or they will go out of business. It is not up to the new companies to subsidize the old companies and their suppliers.

Most of what Michael Geist says in this post is wrong. He is wrong about Steven Guilbeault’s thresholds, wrong about its impact on Canadian consumers, wrong about the contribution of the US web giants, wrong about the issue of a level playing field, wrong about the economic impact of the bill and wrong about Canadian cultural sovereignty. No doubt in his new series of posts, Michael Geist will recycle the myths and misconceptions about broadcasting and the Internet that he has been advocating for some time. Tax reform, privacy upgrades, and competition law enforcement have nothing to do with amendments to the Broadcasting Act. Readers are invited to review this reader’s responses to Michael Geist’s various and sundry claims over the last few years in the comments section below his previous blogs on broadcasting policy.

Yes, Canadian television production rose by a total of 8.1% between 2011-12 and 2018-19 (a period of seven years) while foreign location and film and television service production increased by 288.0%. This latter statistic includes conventional Hollywood filmmaking and is essentially attributable to the generous tax credits that competitive provincial governments offer run-away US productions. In 2018-19, average budgets in French-language television fiction and documentaries were lower than in 2010-11. In 2018-19, television production in Ontario had increased by 4.1% over the seven years since 2011-12.

The trends in Canadian television production financing over the last five years are clear. Private sector broadcaster licence fees, Canada Media Fund contributions and other private sources of production financing are declining. Public broadcaster licence fees (especially those of the CBC/Radio-Canada as a result of the federal government’s increase in funding) and other public sources of public financing are increasing to compensate, but this cannot go on for long.

Michael Geist continues to cite CRTC chair Ian Scott’s outburst concerning Netflix, but unfortunately Mr. Scott is a telecom guy unfamiliar with Canadian broadcasting. Like Michael Geist, he confuses the Canadian production sector with foreign location shooting in Canada. The Internet giants, which Michael Geist wants to release from Canadian law and regulations, will not make a substantial contribution to Canadian national identity and cultural sovereignty unless and until constrained to do so. And as I mentioned in my comment on Michael Geist’s November 3rd blog, Netflix appears to be quite willing to accept Canadian regulatory authority, as the web giants have generally done abroad when and where governments intervene.

I agree. All correct.

Take the Good Doctor/Bull just to name a couple both filmed in Canada creating thousands of jobs but you think they should be kicked out.

No one thinks that. Quite the opposite. We think the service production business creates an opportunity to make more original production as well.

The point is that we have to differentiate between Canadian and service when we look at the systemic issues. Service is driven primarily by the local environment from labour costs to tax credits and the overall increase of production right now. Cancon is more structural.

It’s the same old arguments – M. Geist is an idiot and our national identity is threatened by American content unless the Guardians of Cultural Sovereignty get a slice of the pie.

Why don’t you produce some evidence that official Canadian content actually contributes to our national identity rather than just enriching the entitled. All I ever see is production levels. There is never any evidence that the billions spent on Canadian content is well spent.

We are one of the largest exporters of content in the world. I attend major markets all over the world and I don’t think anyone would question that Canada is major player. The “national identity” test is pretty subjective. Is it Shitt’s Creek winning Emmys or Anne of Green Gables?

One thing that does distinguish us is that we are probably the only country that questions their need to make tell their own stories. Probably the constant propaganda from a few of the Cable owners who didn’t want to pay into the Canadian Media Funds.

Pingback: News of the Week; November 25, 2020 – Communications Law at Allard Hall