The government’s online harms bill, led by Canadian Heritage, is likely to be introduced in the coming weeks. My series on why the department faces a significant credibility gap on the issue opened with a look at its misleading and secretive approach to the 2021 online harms consultation, including its decision to only disclose public submissions when compelled to do so by law and releasing a misleading “What We Heard” report that omitted crucial information. Today’s post focuses on another Canadian Heritage consultation which occurred months later on proposed anti-hate plans. As the National Post reported earlier this year, after the consultation launched, officials became alarmed when responses criticizing the plan and questioning government priorities began to emerge. The solution? The department remarkably decided to filter out the critics from participating in the consultation by adding a new question that short-circuited it for anyone who responded that they did not think anti-hate measures should be a top government priority.

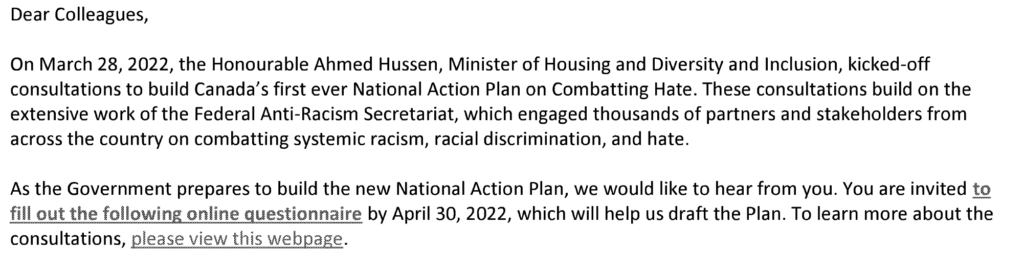

As revealed by the Post and contained in documents released under the Access to Information Act, the plan was launched by Minister Ahmed Hussen (the same minister who oversaw the slow response to funding for an anti-semite as part of the same anti-hate program) with an invitation from the head of the federal anti-racism secretariat to participate in the consultation survey.

Canadian Heritage ATIP A-2022-00029

The first hint that the department was concerned with responses that did not support its policies arose days after the consultation survey was launched with officials noting that critics were not the target of the survey. In other words, the department was only interested in hearing from those that supported its policy priorities.

Canadian Heritage ATIP A-2022-00029

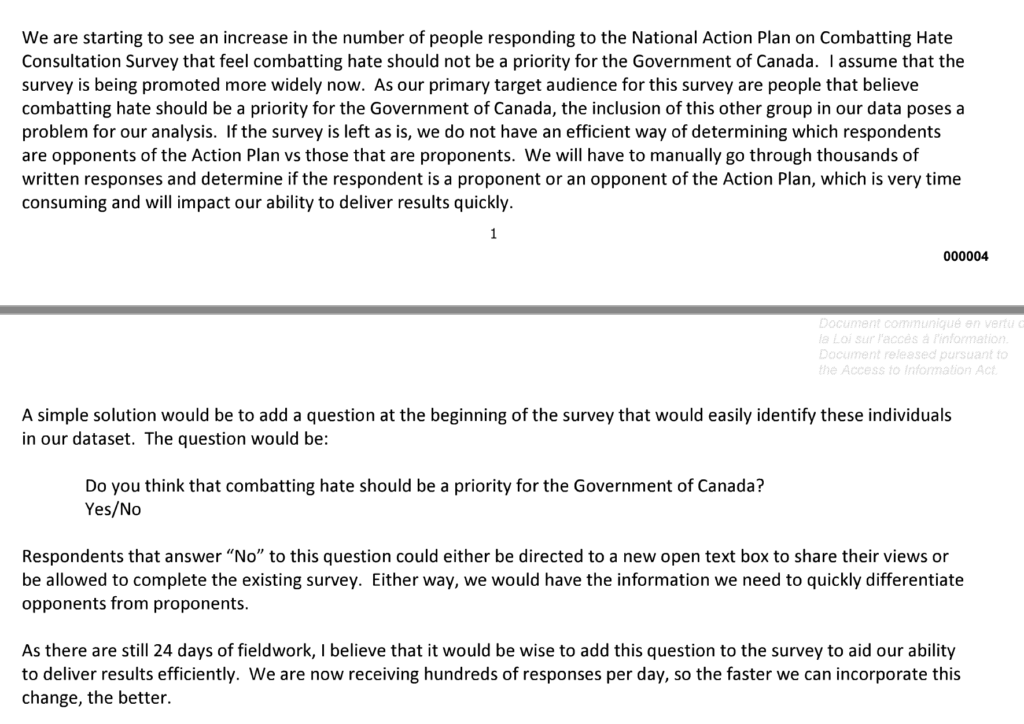

The solution was to add another question: “do you think combatting hate should be a priority for the Government of Canada?” Canadians that said no would be directed to the end of the survey and blocked from providing their views on various policy measures. In fact, critics were not only filtered out, they were called “non-allies” in one email by supposedly non-partisan officials.

Canadian Heritage ATIP A-2022-00029

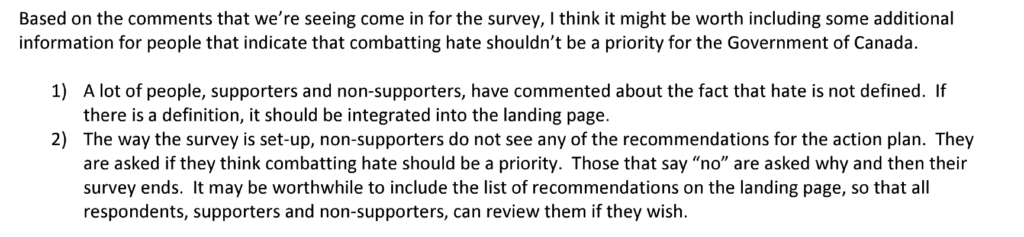

Notably, officials knew that not all responses being filtered out were critics of the plan or prioritizing anti-hate measures. In another email, officials acknowledge that some of the responses indicating that anti-hate program was not a policy priority could have resulted from the failure to even define the meaning of “hate” for the purposes of the survey. In fact, the officials noted that the definitional ambiguity was a potential concern for both opponents and supporters of the plan. Moreover, officials admitted that their approach had the effect of denying access to any policy specifics once a respondent indicated that anti-hate policies were not a policy priority.

It should go without saying that filtering out critical responses from a government consultation renders the entire consultation unusable. But it is worse than that. Canadian Heritage officials describe critics as “non-allies” and actively worked to exclude their views from their policy making process. If that is the approach on a public consultation, what kind of credibility does the department have when it introduces legislation that may have been based on those results? The answer is obvious: Canadian Heritage has forfeited much of its credibility with a policy process that actively sought to exclude anyone who disagreed with its priorities.

The problem is that credibility has no standing in anything the government does or doesn’t do.

Even if the ministry has no credibility, they are able to ram through their legislation, complete with consultation theatre and lobbyist applause.

In the real world, the manner in which Canadian Heritage conducts itself is called fraud and is illegal and punishable.

This fraudulent activity will continue to happen in our legislative process until it is also made illegal and punishable.

There’s another big red flag with this survey. Officials noted “A big chunk of the 20-25% of supporters were from a Government of Canada IP address”. Why? Was there an orchestrated plan to distort the results of the survey?

Also, what are government workers doing completing surveys while at work?

I’ve got to agree with the comments here. In essence what we have here is a “pro-forma” consultation, one so that they can say they did one. In my experience governments in Canada tend to do a public consultation so that they can say they did one; depending on which party is in power the media may, or may not, decide to look into it any deeper. It isn’t really a consultation if it is manipulated to confirm a predetermined conclusion.

DB, given that most federal public servants were working from home using government issued laptops, there is no guarantee that they didn’t do it after hours but using the government laptop. The federal employees I know who use a government laptop at home tend to need to VPN into the office for most work (in some cases it was configured to automatically attempt to connect to the VPN). As a result I can’t assume that they were doing it at work. However it would be interesting to see a breakdown of the IPs; of the GoC addresses, how many are Heritage IPs?

The report said …. from a goc IP address. Since the singular was used I’m assuming all the support came from 1 IP address. That makes me wonder if only a few employees got together and each completed multiple surveys.

Where do you get such awesome ideas from great web page and amazing idea it should be promoted more than it is.

I wanted to try a free tip calculator because I really love using it while I tip on different restaurants 🙂