In a day that started with Canadian Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault urging the Senate to focus on passing Bill C-10, Senators from across the political spectrum again signalled that they believe that Guilbeault’s bill requires extensive hearings given the flawed legislative approach in the House of Commons and a resulting bill that raises a wide range of policy concerns. Concerns with Bill C-10 were raised by virtually every Senator to speak during yesterday’s debate: Senator Donna Dasko noted that “public confidence is lacking at this point in time” in the bill, Senator Colin Deacon argued that the government has failed to address the core concerns involving privacy and competition, and Senator Pamela Wallin called the bill “reckless” and urged the government “to go back to the drawing board.” Those speeches came on top of the first day of Senate debate in which Senator Dennis Dawson admitted that “everybody recognizes the bill is flawed” and Senator Paula Simons said the bill reminded her of the Maginot Line.

Two Senator speeches merit particular mention. First, Senator Leo Housakos provided the bookend to the Simons speech with an evisceration of the content of Bill C-10. While the Simons speech raised the big picture questions about the Bill C-10 regulatory approach, Housakos simply destroyed the bill, highlighting the exclusion of important voices from committee hearings and the negative implications of its substantive provisions. At least three elements stood out. First, the impact of removing Section 4.1 from the bill:

The fact that the CRTC doesn’t consider you to be a broadcaster when you upload a video onto YouTube means nothing if they can make YouTube change its algorithms so that next to no one will ever see it. It means nothing if they can instead make people see a video with the kind of content they prefer.

Second, Housakos identified the core concern with discoverability requirements:

by prioritizing some content the CRTC will naturally be de-prioritizing other content in ways that go beyond limiting speech. It will be picking winners and losers.

And who will be the winners and losers? Housakos calls it:

The beneficiaries of that system will be the established well-funded media production companies with the lobbyists and lawyers to work it to their advantage – more gatekeepers – not the independent YouTube performer looking to go viral and become the next Justin Bieber or Lily Singh.

Third, Housakos linked the current success of the Canadian film and television sector with the gatekeepers’ support for Bill C-10:

The problem isn’t a lack of investment in Canadian talent and Canadian stories. The problem, if you see it that way, is that it’s happening without the need for intermediaries like the Canada Media Fund. The middlemen aren’t getting their cut of the pie, and what’s worse for them is that they’re not controlling which artists and which producers are receiving funding. They want to pick the winners and losers. That’s the beauty of the digital age. The success of artists and producers isn’t determined by the gatekeepers.

If the cost of Bill C-10 and the discoverability rules were not bad enough, Senator Julie Miville-Dechêne unintentionally succeeded in demonstrating how Bill C-10’s approach is a solution in search of a problem. After Housakos noted that Netflix’s multi-million-dollar French-language Quebec film Jusqu’au déclin is considered a foreign film, not a Canadian one (placing the spotlight on the archaic Canadian content rules), Miville-Dechêne went back to that film in discussing discoverability:

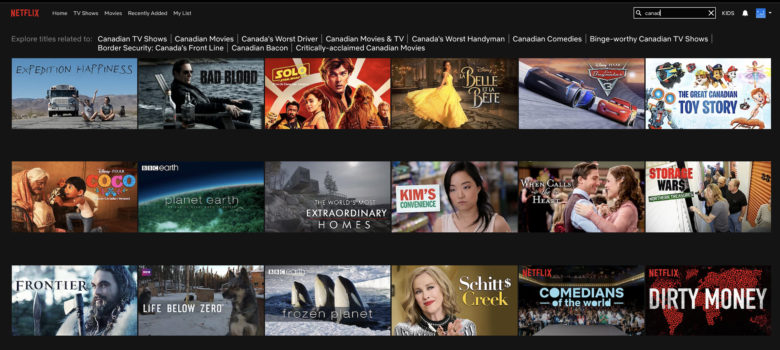

I myself ran into difficulty with Canadian content not being discoverable on Netflix when the first Quebec film produced by Netflix became available on that platform. I couldn’t remember the title of the film, which was Jusqu’au déclin, and it wasn’t among the top recommendations, even though it was a new release. I asked Netflix’s spokespeople why this title wasn’t made more visible for Quebec and Canadian subscribers. I was told that titles are ranked according to the interest displayed by members, and that I could simply have typed in “Canada” and the title would have appeared, but that wasn’t something I was aware of.

Senator Miville-Dechêne’s comment raises at least three issues. First, contrary to the repeated claims that Netflix does not invest in producing Canadian content, films such as Jusqu’au déclin suggest otherwise (the fact that it does not technically qualify as Canadian content is a problem with the Cancon definition system, not Netflix). Second, discoverability of the film does not appear to be a problem since it has been viewed more than 21 million times by people around the world, with more than 95% of viewers outside Canada. Third, the fact that finding Canadian content requires nothing more than typing “Canada” is both obvious (I did a post on the issue years ago) and something that confirms yet again that the Bill C-10 discoverability rules are unnecessary.

The Bill C-10 debate continues in the Senate for one more today later this afternoon.

It’s hard to believe the government has wasted so much time and effort on worrying about how easy it is to find Schitt’s Creek on Netflix. There are so many other equally important issues they could have addressed, like:

1) What to do with all the old bald men who insist on wearing a 3 inch ponytail. Don’t these guys have mirrors?

2) Should politicians receive a royalty every time their name is mentioned in the news. Because isn’t it immoral that news organizations make money off of the backs of politicians?

3) Is the lack of brown cars a sub-conscious sign of discrimination?

4) Should chronic bad hair be considered a disability?

5) How to Canadianize acronyms used in texting. How about LOLeh.

Pingback: Senator's Concerns About Bill C-10 Perfectly Aligns With Freezenet's Earlier Visualization

Hey Michael just wanted to say thank you for writing these articles and expressing how backwards this bill is. As someone who has seen success on Youtube, it really seems like the government is going out of their way to ensure the big three get an unfair advantage on the platforms they fail so hard in.

Conservative appointees of Stephen Harper, such as Leo Housakos and Pamela Wallin, are clearly following the party line. To claim that Bill C-10 can “make people see a video with the kind of content they (the CRTC) prefer” is ridiculous. It does no such thing. To say that “by prioritizing some content the CRTC will naturally be de-prioritizing other content in ways that go beyond limiting speech. It will be picking winners and losers” is dishonest.

The CRTC already has a range of discoverability requirements for linear Canadian television such as the priority list for terrestrial digital programming undertakings (Canadian services are listed before non-Canadian services) and Canadian content requirements for the evening hours on linear digital television programming undertakings (to prevent Canadian content from being restricted to off-peak viewing hours). These kinds of requirements are a promotional device for Canadian content and do not limit or inhibit freedom of choice. The implementation of Bill C-10 would encourage the CRTC to find similar kinds of promotional stratagems for video-on-demand (VOD).

It is disingenuous of Michael Geist to say that “contrary to the repeated claims that Netflix does not invest in producing Canadian content, films such as Jusqu’au déclin suggest otherwise (the fact that it does not technically qualify as Canadian content is a problem with the Cancon definition system, not Netflix).” Nobody is claiming that Netflix doesn’t invest in producing content in Canada. The complaint is that spending by Netflix on certified Canadian content is insignificant compared to what it is spending on runaway Hollywood production (American stories with all-American production elements) located in Canada to take advantage of federal and provincial tax credits. Jusqu’au déclin constitutes 83 minutes of “Canadian” French-language content. It is the first French-language Canadian fiction film produced by Netflix in ten years. This points to an issue in Canadian content certification which will become significant if Bill C-10 becomes law.

Canadian content certification currently requires that the production company producing a film or video production and applying for certification must be a “prescribed taxable Canadian corporation” that is Canadian-controlled. This prerequisite evolved from the Canadian government’s desire to foster a Canadian independent production sector in the 1980 and, as a result, productions by the US-controlled digital media giants are not eligible to be certified as Canadian – even if they fulfil all other Canadian content requirements. If Bill C-10 becomes law, this rule will have to be looked at. Will it continue to be necessary that all Canadian certifiable production in the underrepresented categories of programming (fiction, POV documentaries, variety, children’s, etc.) be produced by Canadian independent production companies? Or will the digital media giants be given a dispensation that has been refused to Canadian broadcasters up to now. Voilà : the elephant in the room. But it will only be become an issue if Bill C-10 becomes law. And there are clearly solutions to this dilemma, if Bill C-10 passes and the situation arises.

The idea that “finding” Canadian content is an easy as typing “Canada” in a Netflix search is naïve and simply misses the point. Such a search will only bring up a list of productions with “Canada” as subject matter. The intention of discoverability requirements is to bring certified Canadian productions to the attention of Canadian viewers those productions that express a Canadian point of view. And the best proxy for this kind of search lies in their creative elements.

TLDR

this wind bag is saying the CRTC is wonderful and we should arrogate more power unto the government class to rule over us

get fucked, bootlicker

The supporters of C-10 come in two categories; those who wiII profit by having the CRTC make the decisions about what wiII be avaiIabIe for viewing, and those who want to have the CRTC shut out the voices with which they disagree.

No one at the CRTC is smart enough to teII me what to watch; nor do they have the right to do it.

After C-10 has been resoIved, I hope someone has saved enough powder to discuss C-36. That one is even worse.

Even North Korea wouId be proud of Justin and his “woke” crew for this one. A biII that pretends it is about “hate speech” but is in fact, just a more focussed effort on censoring Canadians who don’t agree with the current IiberaI narrative; of the CBC take on the issues.

Canadian content certification currently requires that the production company producing a film or video production and applying for certification must be a “prescribed taxable Canadian corporation” that is Canadian-controlled.

amazwed

This is a really wonderful debate and article! I am very happy to read this and have a fun time reading it! Thanks! http://www.concretecontractorsfortsmith.com